There has been some confusion lately regarding how much longer HFCs will be readily available in the U.S. According to the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, developed countries will have to begin phasing down HFCs starting on Jan. 1, 2019 (see Table 1). But the U.S. has not ratified the Kigali Amendment, and a recent court decision found that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) does not have the right to ban HFCs. In response, the Senate has proposed a bill that would provide the EPA with the authority to phase down the manufacture of HFCs in the U.S., but its outcome will likely not be known for quite some time.

Regardless of any pending litigation or legislation, most in the HVACR industry believe it is just a matter of time before HFCs are phased down. That is why many manufacturers are already getting ready for the next generation of refrigerants, which, depending on the application, may include hydrocarbons, HFOs, ammonia, CO2, or something else completely.

WIDESPREAD SUPPORT

The Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute (AHRI), like most others in the HVACR industry, strongly supports the Kigali Amendment, with Francis Dietz, vice president of public affairs, noting that the organization has advocated for the amendment’s HFC phasedown approach for nearly 10 years. What is important to understand about the amendment, he said, is that while it phases down HFCs, it does not phase them out.

“A sufficient worldwide amount of HFCs is necessary for refrigerant blends, which is why this is not a complete phaseout of the chemicals,” said Dietz. “Regardless of whether Kigali is ratified by the U.S., our industry is committed to the phasedown of HFCs.”

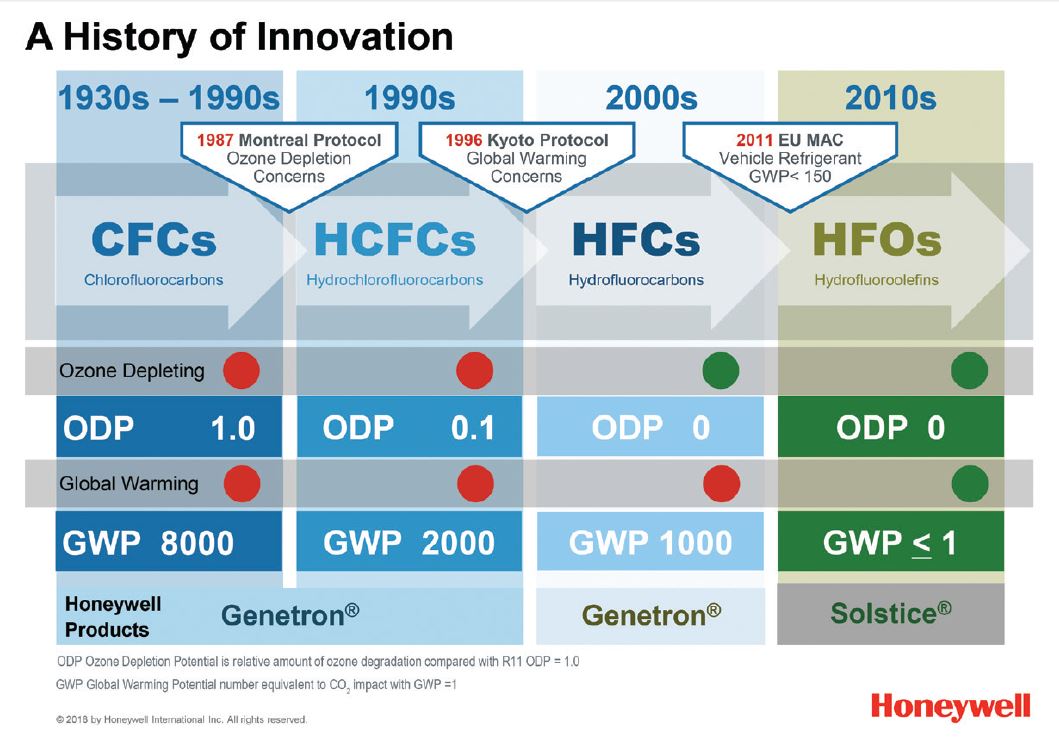

CFCs TO HFOs: Refrigerant transitions have occurred regularly over the last 30 years, as shown here. Graphic courtesy of Honeywell

HVACR manufacturers agree, noting that much of the rest of the world, including the European Union (EU), is already heading down this path and that the U.S. should follow suit. There are numerous benefits to ratifying the Kigali Amendment, said John Hurst, vice president of government relations and communications, Lennox Intl., including improved domestic trade, manufacturing, and job growth.

“The transition from HFCs to new refrigerants is going to happen globally, regardless of the U.S. position on the matter,” said Hurst. “The federal government needs to decide if the U.S. is going to lead the technology transfer to new refrigerants or become the laggard. Failure to ratify the Kigali Amendment would be incredibly short-sighted by the federal government.”

Indeed, maintaining global leadership in HVACR technology is one of the main reasons why the U.S. should ratify Kigali, said Mark Menzer, director of public affairs – North America, Danfoss. In addition, much of the technology produced in the U.S. is supplied to other countries, so manufacturing equipment that utilizes non-HFCs could both improve the balance of trade and save American jobs, he noted.

“The recent study, Economic Impacts of U.S. Ratification of the Kigali Amendment [see sidebar], shows that ratification of the Kigali Amendment could lead to the creation of 33,000 more U.S. jobs by 2027 in manufacturing alone,” said Menzer. “We anticipate the tenets of the Kigali Amendment to be beneficial for the HVACR industry and to result in better, more sustainable equipment for end users.”

Ratifying the Kigali Amendment would also ensure an orderly phasedown of HFCs, as well as provide a measure of long-term regulatory certainty that is needed in the HVACR industry, explained Paul Doppel, senior director, industry and government relations, Mitsubishi Electric US Inc.’s Cooling & Heating Division. Implementing the Kigali Amendment at a national level is also preferable to states implementing their own measures to regulate refrigerants, which is starting to happen across the country.

“California has already begun this process and intends to phase out refrigerants based on global warming potential on an accelerated schedule different from that in the Kigali Amendment, which would be harmful to our industry,” said Doppel.

To see how an accelerated phasedown schedule could play out, one need only look at the EU, which has been struggling with shortages and sky-high prices due to severe cuts in HFC (called F-gases there) production over the last three years. There are some differences in the EU, as not only is its F-gas phasedown schedule more aggressive than the Kigali Amendment timeline, it also includes bans of certain applications on top of the phasedown, said Matt Ritter, global business director, Arkema.

“This combination can potentially create an environment that can starve existing demand and could lead to noncompliance, which is why the U.S. should ratify the Kigali Amendment,” said Ritter. “This would provide defined timelines that allow for adequate development of new technology, training of key personnel, and market acceptance by the users. Ultimately, the Kigali Amendment will improve the economy, expand OEM portfolios and consumer options, and expand the use of more efficient technology.”

WHAT COMES NEXT?

Manufacturers are not waiting for the government to act on HFCs, as many have already started the transition to alternative refrigerants. This is especially true in the supermarket industry, which has been phasing down the use of R-22, R-404A, and other refrigerants for quite a while, said Chris LaPietra, vice president and general manager of stationary refrigerants, Honeywell Fluorine Products.

“The supermarket chains that switch to the lower-GWP products, such as HFOs, usually gain energy savings up to 10 percent better performance and lower environmental impact without sacrificing the safety,” said LaPietra. “Customers who started adopting HFOs early are already enjoying the benefits these products bring, be it lower energy bills, lower maintenance costs, or lower carbon footprint.”

Table 1: HFC phasedown schedule for developed countries

| Year | Production/Consumption Cap (relative to baseline) | Reductions in Production/Consumption |

| 2017-2018 | None | None |

| 2019 | 90% | 10% |

| 2024 | 60% | 40% |

| 2029 | 30% | 70% |

| 2034 | 20% | 80% |

| 2036 | 15% | 85% |

The refrigeration industry has definitely been a leader in transitioning to alternative refrigerants, with some OEMs already offering a full line of low-GWP solutions that include fluorocarbons, hydrocarbons, ammonia, and CO2, said Menzer. Most air conditioning OEMs are working to optimize their future offerings with low-GWP refrigerant replacements as well, but finding a replacement for R-410A in residential and light commercial applications, in particular, is a challenge, because the current candidates are all classified A2L refrigerants.

One reason for the current challenge is the absence of building and fire codes that would allow for new refrigerants (many of which are flammable) to be more broadly accepted, said Menzer. In addition, there is a lack of clarity on the role of the EPA, which was told by the courts that it exceeded its authority when it delisted HFCs.

“It is also critical that any HFC phasedown align with future efficiency standards and regulations in order to avoid uncoordinated goals that make compliance difficult and inefficient for manufacturers and potentially expensive for end users,” he said.

The phasedown of R-410A will be challenging, agreed Ritter, and there will likely not be one substitute refrigerant that acts as a drop-in replacement for all applications. That is because the needs vary by application, so the industry will need to consider multiple refrigerant solutions.

“For most applications, low-GWP HFCs, HFOs, and HFC/HFO blends will offer the best combination of performance, safety, efficiency, and environmental protection,” said Ritter. “But there are applications, particularly where the refrigerant charge is small, where hydrocarbons may be the product of choice. The beauty of the Kigali Amendment is that it does not ban materials, but rather lets the markets decide the most appropriate substitutes while achieving the necessary environmental benefits. There is room for all categories, and we should let the market decide what works best in each application.”

AHRI, along with its partners, is helping this process along, having developed a research program in 2011 that is working on identifying alternatives to HFCs. The organization is currently in the process of conducting real-world testing on the most promising replacements, and Dietz said that it is apparent there will be several alternatives from which manufacturers may choose, depending on the application.

“At this point, it is unclear which of the identified alternatives will end up being used for the equipment in which R-410A is currently used,” he said. “That will be up to each manufacturer to decide.”

For residential systems, one possible short-term replacement for R-410A may be R-32, which is already being widely used in Asia and Europe. Mitsubishi Electric, for example, introduced products in Japan in 2013 that utilize R-32. Another promising replacement may be R-452B, which has similar performance properties to R-32 but has exhibited slightly better flammability characteristics, according to Doppel.

“After 2029, [when the Kigali Amendment] calls for a reduction in HFCs as a percentage of baseline from 60 to 30 percent, we expect to see a transition to usage of natural refrigerants, such as hydrocarbons, carbon dioxide, and low-GWP synthetics, such as HFOs,” said Doppel. “HFCs will likely not be allowed for use in new equipment after this date.”

Lennox has also been proactive in transitioning out of HFC refrigerants, having already introduced several non-HFC products in various categories. As Hurst noted, the primary challenges involved with phasing down HFCs are similar to other transitions the HVACR has already experienced, such as efficiency, reliability, safety, and durability. But transitions can be much more difficult if there is not a proper plan in place that contains thorough implementation guidelines and allows enough time for the industry to prepare for a phasedown, he contends. And the Kigali Amendment provides those safeguards.

“The Kigali Amendment lays out a rational phasedown schedule; otherwise, the HVACR industry wouldn’t have supported it to begin with,” said Hurst. “The amendment provides a clear timeline at the federal level and avoids a patchwork of state-level regulations and timelines. The U.S. ratification would provide certainty and the ability to plan for an orderly transition, which would reduce transition costs for consumers.”

The industry has been down this road before, both with CFCs and HCFCs, so HVACR manufacturers are adept at handling these transitions. And in both of those situations, there were clear guidelines regarding the phaseout schedule. Manufacturers want that same certainty with the HFC phasedown, which is why they overwhelmingly support ratifying the Kigali Amendment.

Report Details Economic Benefits of Kigali Ratification

The Alliance for Responsible Atmospheric Policy and the Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute (AHRI), recently released their comprehensive study, Economic Impacts of U.S. Ratification of the Kigali Amendment, supporting the ratification of the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, which calls for a phasedown in the production and consumption of HFCs worldwide.

The report states that the Kigali Amendment gives American companies an advantage in technology, manufacturing, and investment, which will lead to job creation. The economic analysis indicates that U.S. implementation of the Kigali Amendment is good for American jobs, and it will both strengthen America’s exports and weaken the market for imported products, while enabling U.S. technology to continue its world leadership role.

According to the study:

- The Kigali Amendment is projected to increase U.S. manufacturing jobs by 33,000 by 2027, increase exports by $5 billion, reduce imports by nearly $7 billion, and improve the HVACR balance of trade;

- With Kigali, U.S. exports will outperform, increasing U.S. share of global market from 7.2 to 9 percent;

- Fluorocarbon-based manufacturing industries in the U.S. directly employ 589,000 Americans, with an industrywide payroll of more than $39 billion per year. The fluorocarbon industry in the U.S. indirectly supports 494,000 American jobs with a $36 billion annual payroll; and

- The U.S. fluorocarbon using and producing industries contribute more than $205 billion annually in direct goods and services, provide employment to more than 2.5 million individuals, and contribute overall economic activity of $620 billion to the U.S. economy.

The HVACR industry historically has been the global leader, building on a strong domestic base and expanding the use of new technology around the world, and the changes driven by the Montreal Protocol have strengthened and expanded that U.S. leadership. Ratification of Kigali is crucial to continuing that pattern and maintaining U.S. leadership, noted the report, and without Kigali ratification, growth opportunities will be lost, along with the jobs to support that growth; the trade deficit will grow, and the U.S. share of global export markets will decline.

“This study illustrates in a very concrete way the fact that U.S. ratification of the Kigali Amendment is good for American jobs, good for the economy, and crucial for maintaining U.S. leadership across the globe,” said Stephen Yurek, CEO and president of AHRI. “It will help American companies capture a large portion of the projected $1 trillion global market for the next generation of innovative, energy-efficient products and equipment.”

Publication date: 6/4/2018

Want more HVAC industry news and information? Join The NEWS on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn today!

Report Abusive Comment