Despite the influx of federal funding around indoor air quality for K-12 schools, the most common ventilation strategies over the past year remain lower-cost options: fixing existing HVAC systems, opening windows and doors, or just taking the class outdoors.

The CDC recently examined reported ventilation improvement strategies among a sample of K-12 public schools in the United States using data collected from the National School COVID-19 Prevention Study (NSCPS), a web-based survey administered to school-level administrators beginning in the summer of 2021. The CDC examined wave 4 (420 schools) data from February 14-March 27, 2022. The study examines 11 ventilation improvement strategies in schools and on school-based transportation. The percentage of students eligible for free or reduced priced meals during 2019-20 served as a proxy for school poverty level. School locale was categorized as city, suburban, town, or rural according to NCES.

Click chart to enlarge

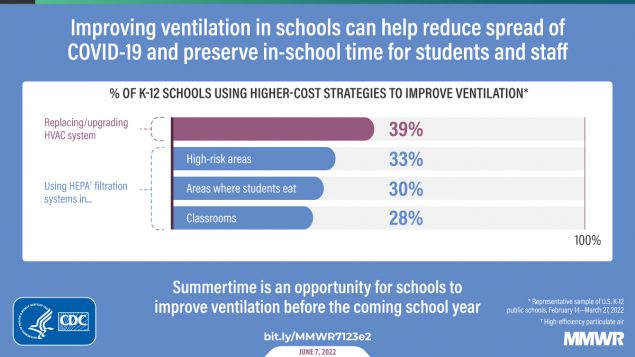

According to a new CDC study, just over a third of U.S. school districts updated or replaced their HVAC systems in the past year. (Courtesy of CDC)

Improved ventilation can reduce the concentration of infectious aerosols and duration of potential exposures, is linked to lower COVID-19 incidences, and can offer other health-related benefits (such as better measures of respiratory health, such as reduced allergy symptoms). Whereas wind currents dissipate SARS-CoV-2 outdoors, ventilation systems provide that protective airflow and filtration indoors.

While there are a number of ways schools can pay to improve their ventilation strategies, the most frequently reported ventilation improvement strategies were lower-cost strategies when it was safe to do so:

- Relocating activities outdoors (73.6%).

- Inspecting and validating existing heating, ventilation, and HVAC systems (70.5%).

- Opening doors (67.3%).

- Opening windows (67.2%).

A smaller portion of schools reported more resource-intensive strategies:

- Replacing or upgrading HVAC systems (38.5%).

- Using HEPA filtration systems in classrooms (28.2%) or eating areas (29.8%).

Of all the data collected, the report shows that rural and mid-poverty-level schools were less likely to report resource-intensive strategies:

- Rural schools were less likely to use portable HEPA filtration systems in classrooms (15%) than were city (37.7%) and suburban schools (32.9%).

- Mid-poverty-level schools were less likely than high-poverty-level schools to have replaced or upgraded HVAC systems (32.4% versus 48.8%).

The least frequently reported ventilation strategies were resource-intensive:

- Using portable HEPA filtration systems in classrooms (28.2%).

- Using HEPA filtration systems in areas where students eat (29.8%).

- Using portable HEPA filtration systems for high-risk areas (32.8%).

- Using fans to increase effectiveness of windows opened (37.0%).

- Replacing or upgrading HVAC systems since the beginning of the pandemic (38.5%).

Six ventilation strategies significantly differed by locale:

- City schools were less likely to report opening windows (53.9%) than were suburban (69.5%), town (75.3%), and rural (73.5%) schools.

- City schools were less likely to use fans to increase effectiveness of opening windows (26.1%) than were town (43.0%) and rural (43.3%) schools.

- City schools were less likely to open windows on school buses (54.5%) than were rural schools (72.9%).

- Rural schools were less likely to use HEPA filtration systems in areas where students eat (19.1%) or to use portable HEPA filtration systems in classrooms (15.6%) than were city (33.4% and 37.7%, respectively) and suburban schools (33.2% and 32.9%, respectively).

- Rural schools were less likely than were city schools to use portable HEPA filtration systems for high-risk areas (22.0% versus 44.7%).

Six ventilation strategies significantly differed by school poverty level:

- Mid-poverty schools were less likely than were low-poverty schools to have inspected and validated existing HVAC systems (66.0% versus 83.0%).

- Mid-poverty schools were less likely than were high-poverty schools to have replaced or upgraded HVAC systems (32.4% versus 48.8%), relocated activities outdoors when possible (69.1% versus 83.0%), and increased ventilation in areas where students eat (37.8% versus 55.4%).

Mid-poverty schools were less likely to use portable HEPA filtration systems in classrooms (20.5%) and use portable HEPA filtration systems for high-risk areas (24.1%) than were low-poverty (43.8% and 49.8%, respectively) and high-poverty schools (36.0% and 44.7%, respectively).

Report Abusive Comment