At the recent AHR Expo in Orlando, Florida, Emerson held several seminars on the topic of current and future refrigerant regulations in the U.S. The information was timely, as there are many questions and concerns about the HFC phasedown legislation taking place at the federal and state levels.

This is evidenced by a recent survey from Emerson, which asked about proposed laws that will likely require the use of lower-GWP refrigerants in air conditioning equipment as early as January 2023. About 58 percent of contractors and wholesalers surveyed said they have at least a basic understanding of the requirements. While 73 percent said this requirement will affect their company’s daily operations, about two-thirds of contractors surveyed have not taken action yet to prepare.

In comments provided with the survey, contractors and wholesalers stated they have concerns not only about getting educated themselves on these regulations, but also over what they will need to do to help their customers get through these changes. Emerson’s educational sessions explained the current refrigerant regulatory landscape, as well as what the lower-GWP mildly flammable refrigerants could mean for the HVACR industry.

REGULATORY LANDSCAPE

Jennifer Butsch, manager of regulatory affairs at Emerson, offered an overview of the refrigerant regulatory landscape in the U.S. Right now, everything is in a bit of limbo. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — which mandated the phaseout of ozone-depleting HCFCs such as R-22 under rules 20 and 21 of its Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) program — was told by the courts that it did not have the authority to phasedown HFCs, which are non-ozone depleting substances but have a high GWP.

That means there is currently no federal program in place that regulates the use of HFCs. Hosever, states are stepping into the void and implementing all or part of EPA’s SNAP rules 20 and 21. California was the first state to adopt these rules, followed by Washington, Vermont, and New Jersey. Colorado, Oregon, and Hawaii all have recently announced that they to intend to adopt SNAP rules 20 and 21 as well.

“As an industry, we understand the need of the states to move forward; however, we do ask that they try to be consistent in approach, because as we manage a state-by-state approach, it becomes a little more complicated,” said Butsch. “To prove this point, we now have four states that have adopted into state law SNAP rules 20 and 21, and there are four different implementation dates on when these would take effect.”

For example, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) is proposing a GWP limit of 750 for all new stationary air conditioning systems (residential and commercial) starting Jan. 1, 2023, and the same GWP limit for new chillers, effective Jan. 1, 2024. On the commercial refrigeration side, there is a proposed GWP limit of 150 for new stationary refrigeration systems containing more than 50 pounds of refrigerant, starting on Jan. 1, 2022.

Regarding commercial refrigeration regulations in California, there was some pushback from food retailers who were concerned about meeting the new <150 GWP limit in existing stores, said Dr. Rajan Rajendran, vice president of system innovation center and sustainability at Emerson.

“The new proposal states that if a food retailer has more than 20 stores in their fleet total, then they have to reduce their weighted average GWP to 1,400, or a 55 percent reduction in greenhouse gas potential by 2030,” he said. “If a company has 20 or more stores, then partway through, they have to show that they’re making some progress. If a company has fewer than 20 stores, they don’t have to show the progress halfway through, but they still have the same end goal of averaging a median 1,400 GWP or 55 percent reduction in greenhouse gas potential by 2030.”

Rajendran added that while this regulation only affects California at the moment, other states are taking note and may eventually adopt similar legislation.

“We have to assume that other states are looking at California, so people are going to take it up,” he said. “Even if you don’t have a single store in California, you still need to be concerned about this, because what happens in California may happen in Maine. So please give any comments you have to CARB.”

Butsch noted that the House and Senate have proposed bills that would give EPA the authority to regulate HFCs, so there appears to be some movement at the federal level.

“There’s a lot of support from the industry for these bills,” she said. “It’s important to note that there is no federal preemption tied to either of these bills at the moment, which means it wouldn’t prohibit California from doing what they’re doing. They could still move faster — any state could still move faster. Our hope is that if there were a federal HFC regulation put in place with a phasedown schedule, it would be possible to phase down together. That would reduce a lot of the complexity that we’re seeing on a state-by-state approach.”

ALTERNATIVE REFRIGERANTS

With the federal government and various states looking to phase down high-GWP refrigerants such as R-410A and R-404A, the industry is searching for lower-GWP solutions that can be used in their place (see Figure 1). Some emerging candidates for stationary air conditioning systems are R-32 and R-454B, but both of these are mildly flammable and, as of yet, not approved for use in these applications. For commercial refrigeration, nonflammable alternatives such as R-448A and R-449A are available, but their higher GWP may not be an option in states such as California. In these instances, ultra-low GWP options such as CO2, ammonia, and propane may need to be considered.

Click chart to enlarge

FIGURE 1: Refrigerant alternatives trend toward lower GWP. PHOTO COURTESY OF EMERSON

“When you start talking about CO2, ammonia, propane, or any A2L refrigerant, you have to be open to making system architecture changes,” said Rajendran. “We have to look at these lower-GWP options as opportunities for us to improve the system and make the efficiency better, and perhaps even make it easier to service.”

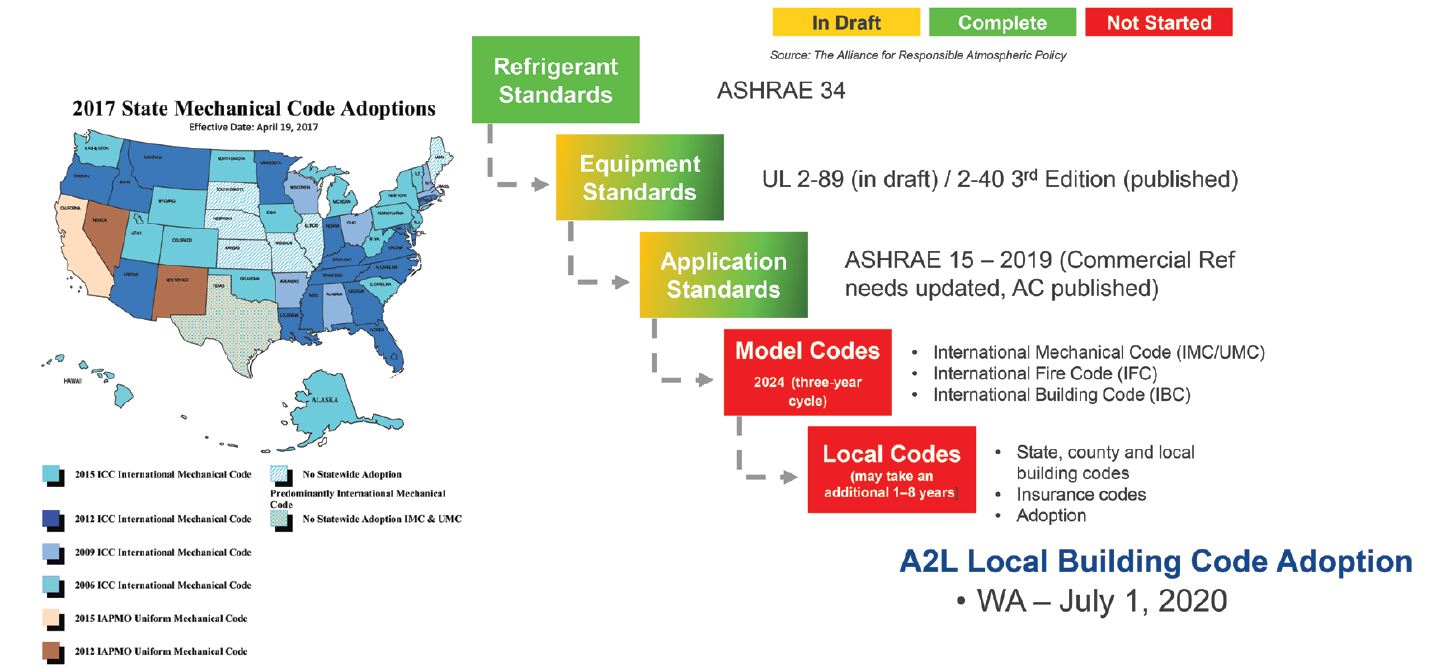

Now that the industry is moving from A1 refrigerants, which are nonflammable, to A2L (mildly flammable) and A3 (flammable) refrigerants, equipment will need to be redesigned, and there will also be a need for new codes and standards. To understand the difference between the two, Butsch explained that standards are developed by technical committees, usually through organizations like ASHRAE, while codes are concerned with enforcement as well as how the end user will be impacted. Figure 2 shows the long and winding road that refrigerants must take in order to be approved and incorporated into building codes.

Click chart to enlarge

FIGURE 2: U.S. safety standard development continues to be a work in progress. PHOTO COURTESY OF EMERSON

“ASHRAE 34 (Designation and Safety Classification of Refrigerants) was the first step, and this refrigerant standard applies to air conditioning and commercial refrigeration,” she said. “Once the refrigerant classification was listed in ASHRAE 34, it allowed for UL safety standards to proceed. The product safety standard, UL 2-40 third edition, which was published in November 2019, did pull in A2Ls and allow for certain charges of A2Ls along with some mitigation. The 2019 edition of ASHRAE 15 (Safety Standard for Refrigeration Systems) also pulled in the ability to use A2Ls in comfort cooling and machine room applications. Now we’ve hit a stop with the model code, as both ASHRAE 15-2019 and UL 2-40 third edition were not accepted into the 2021 model code.”

While it can take a really long time for states to adopt building or model codes, Butsch noted that some states are circumventing the process and adopting ASHRAE and UL standards directly into their model codes.

“Just this year, Washington state went around the model code and adopted UL 2-40 third edition and ASHRAE 15-2019 directly into their state codes,” she said. “They have paved the way to allow A2Ls to be used in comfort cooling in their state. Keep in mind they’re not requiring it — there is no proposal like California to require a lower GWP limit. However, it does allow simultaneous installation of R-410A equipment or the new alternative fluid.”

Butsch concluded the seminar by noting that while the industry has successfully transitioned to new refrigerants in the past, many of the new options are mildly flammable, which makes this transition different from those experienced in the past.

“We’ve done a lot of work to get where we’re at so far, but clearly, we’re not finished,” she said. “There’s a lot of work to be done, and 2020 is really going to be a pivotal year for us. We have a lot of codes and standards work to do, but we’re very hopeful for the HFC refrigerant bill that’s in the federal process right now. That would definitely simplify the process.”

See more articles from this issue here!

Report Abusive Comment