There are three main reasons why a compressor will simultaneously have a low head pressure and a high suction pressure: Bad (leaky) compressor valves, worn compressor rings, and a leaky oil separator.

LEAKY COMPRESSOR VALVES

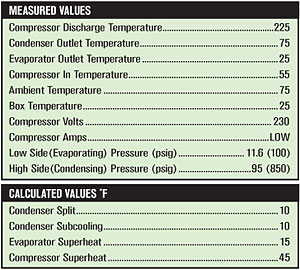

A compressor's valves (Fig. 1) may become inefficient from being warped or having carbon and/or sludge deposits on them preventing them from sealing because of: slugging of refrigerant/oil; moisture and heat causing sludging problems; migration and flooding problems; overheating the compressor; acids/sludges in the system deteriorating parts; TXV set wrong, too little superheats; and undercharge. Below is a service checklist for a compressor with valves that are not sealing.

COMPRESSOR WITH LEAKY VALVES

Many symptoms can be present, making it hard to diagnose the problem. Higher than normal discharge temperatures usually indicates a discharge valve that isn't seating properly because it has been damaged. It will cause the head pressure to be low. Refrigerant vapor will be forced out of the cylinder and into the discharge line during the upstroke of the compressor.On the down stroke, this same refrigerant that is now in the discharge line and compressed will be drawn back into the cylinder because of the discharge valve not seating properly. This short cycling of refrigerant will cause heating of the discharge gases over and over again, causing higher than normal discharge temperatures.

However, if the valve problem has progressed to where there is hardly any refrigerant flow rate through the system, there will be a lower discharge temperature from the low flow rate.

Low condensing (head) pressures are found often because some of the discharge gases are being short cycled in and out of the compressor's cylinder, which causes a low refrigerant flow rate to the condenser. This will make for a reduced heat load on the condenser thus reducing condensing (head) pressures and temperatures.

Normal to high condenser subcooling indicates there will be a reduced refrigerant flow through the condenser, thus through the entire system because of components being in series. Most of the refrigerant will be in the condenser and receiver. This may give the condenser a bit higher subcooling.

Normal to high superheats are a problem because of the reduced refrigerant flow through the system. The TXV may not be getting the refrigerant flow rate it needs. High superheat may be the result. However, the superheat may be normal if the valve problem is not real severe.

High evaporator (suction) pressure causes refrigerant vapor to be drawn from the suction line into the compressor's cylinder during the downstroke of the compressor. However, during the upstroke, this same refrigerant may sneak back into the suction line because of the suction valve not seating properly. The results are high suction pressures.

Low amp draw is caused from the reduced refrigerant flow rate through the compressor. During the compression stroke, some of the refrigerant will leak through the suction valve and back into the suction line reducing the refrigerant flow. During the suction stroke, some of the refrigerant will sneak through the discharge valve because of it not seating properly, and get back into the compressor's cylinder.

In both situations, there is a reduced refrigerant flow rate causing the amp draw to be lowered. The low head pressure that the compressor has to pump against will also reduce the amp draw.

WORN COMPRESSOR RINGS

A second reason why a compressor will simultaneously have a low head pressure and a high suction pressure comes when the compressor rings (Fig. 2) are worn and high side discharge gases leak through them during the compression stroke giving the system a lower head pressure. Because discharge gases have leaked through the rings and into the crankcase, the suction pressure will also be higher than normal. The resulting symptom will be a lower head pressure with a higher suction pressure. The symptoms for worn rings on a compressor are very similar to leaky valves.LEAKY OIL SEPARATOR

A third reason is when the oil level in the oil separator becomes high enough to raise a float. An oil return needle is opened, and the oil is returned to the compressor crankcase through a small return line.The pressure difference between the high and low sides of the refrigeration system is the driving force for the oil to travel from the oil separator to the compressor's crankcase. The oil separator is in the high side of the system and the compressor crankcase in the low side. The float-operated oil return needle valve is located high enough in the oil sump to allow clean oil to automatically return to the compressor's crankcase. Only a small amount of oil is needed to actuate the float mechanism, which ensures that only a small amount of oil is ever absent from the compressor crankcase at any given time.

When the oil level in the sump of the oil separator drops to a certain level, the float forces the needle valve closed. When the ball and float mechanism on an oil separator goes bad, it may bypass hot discharge gas directly into the compressor's crankcase. The needle valve may also get stuck partially open from grit in the oil. This will cause high pressure to go directly into the compressor's crankcase causing high low-side pressures and low high-side pressures.

John Tomczyk is a professor of HVACR at Ferris State University, Big Rapids, Mich. He can be reached by e-mail at tomczykj@tucker-usa.com.

Publication date: 04/03/2006

Report Abusive Comment