As a result of the electrification trend, more homeowners are choosing to replace their gas furnaces with heat pumps. However, this type of retrofit can be complex and expensive, as discussed in the first part of this article. For example, proper sizing, electrical upgrades, and reliable backup heat are all critical factors that must be taken into account to ensure a successful outcome for the customer.

The second part of the article will explore the energy efficiency, payback, and comfort that homeowners can anticipate when replacing their gas furnace with a heat pump. Contractors should take the time to educate customers about the expected performance of their new heat pump, in order to prevent any surprises or dissatisfaction with the system after the installation is complete.

Efficiency and Payback

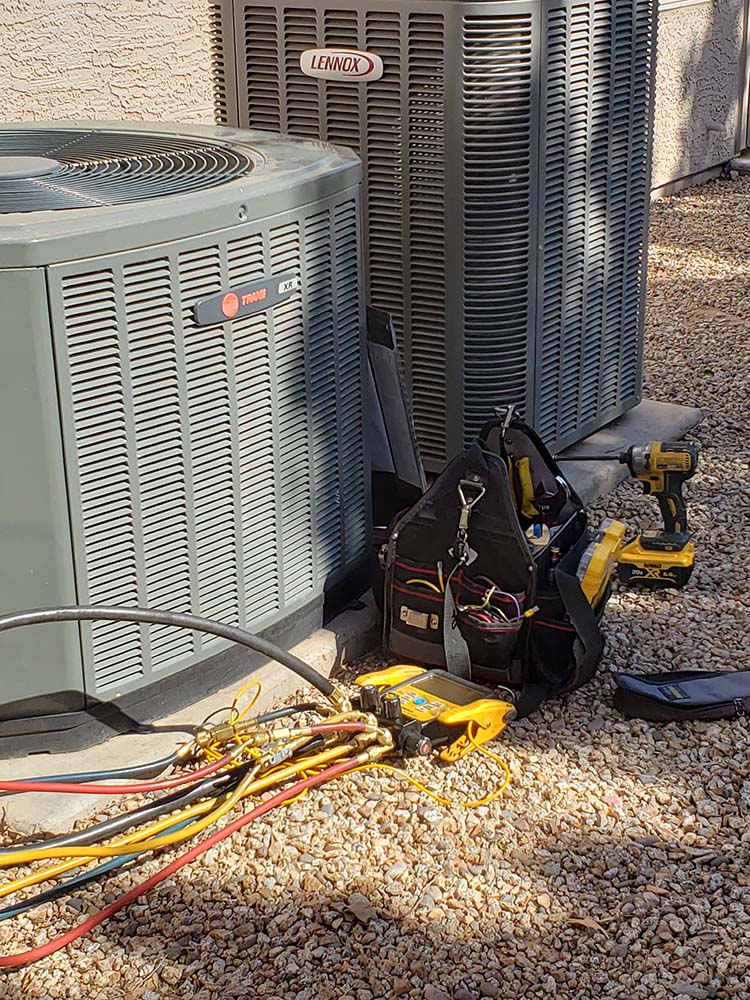

FURNACE REPLACEMENT: As a result of the electrification trend, more homeowners are choosing to replace their gas furnaces with heat pumps. (Staff photo)

Unlike gas furnaces, which burn fuel in order to create heat, heat pumps use electricity to transfer heat, rather than generate it. This gives them mechanical leverage, resulting in higher efficiencies when compared to other heating systems, said Mark Reding, ducted systems product manager II at Johnson Controls.

“For example, a heat pump with a seasonal coefficient of performance of 3 will produce 3 Btu of heat for every Btu of electricity consumed on site,” he said. “A 95% AFUE furnace, by comparison, will generate 0.95 Btu of heat for every Btu of natural gas consumed. The energy efficiency of the heat pump usually translates to lower utility bills and lower source emissions, but electricity rates, natural gas rates, and emissions from electricity will vary by location, so it is important to analyze each project to get an accurate picture of the benefits and costs.”

A homeowner’s location definitely matters, because while the energy efficiency of a heat pump may be three to four times higher than the efficiency of furnace, in many parts of the country, electricity is often much more expensive than natural gas for the equivalent amount of energy, said Ben Lipscomb, P.E., director of engineering and utility programs at National Comfort Institute (NCI).

“So in many cases, the fuel cost difference negates the efficiency advantage, and a customer’s utility bill will remain about the same or even go up some,” he said. “In some areas with moderate climates and electricity prices, there are still bill savings to be had.”

That is why the payback for a new heat pump can be so variable — it depends on a lot of factors, including the climate and the relative prices of electricity and gas, said Lipscomb.

“In the best circumstances, a heat pump might pay for itself in 10 years or so. In the worst circumstances, the heat pump will cost more to operate and will therefore never pay for itself,” he said. “However, the math is much more favorable for heat pumps if you compare to a more expensive fuel such as propane.”

The payback can also depend on the building construction and usage, as well as the efficiency of the equipment that is being installed versus what is being replaced, said Tim Brizendine, director of product management at Lennox.

“For example, replacing an 80% gas furnace that runs on propane with a high-efficiency heat pump in a cold climate with low electricity rates can have a very quick payback, while replacing a high-efficiency natural gas furnace with a standard efficiency heat pump in a milder climate with low natural gas costs and above-average electricity costs will net a poor payback,” he said.

Comfort

director of engineering and utility programs

National Comfort Institute

While comfort can be subjective, it is important for homeowners to understand that furnaces generally produce warmer air than heat pumps, particularly in winter as outdoor temperatures decrease. That is why people may perceive the gas furnace as being more comfortable on a chilly winter day, even if the two different systems are conditioning the home to the exact same temperature, said Lipscomb.

Tim Brizendine, director of product management at Lennox, agreed that from a comfort standpoint, gas furnaces generally provide warmer air than heat pumps.

“However, newer heat pumps (particularly variable-speed heat pumps) can offer similar supply air temperatures to a furnace. Depending on the furnace that was installed, the heat pump can offer more consistent temperatures than a single-stage furnace that quickly cycles on and off and creates larger temperature swings.”

Some homeowners may not be aware of the supply temperature difference in winter, so they may perceive the heat pump as being less comfortable, said Reding.

“But ductwork design, discharge registers, and airflows will all influence how an occupant perceives comfort.”

Humidity control is also part of the comfort equation. Reding said that for homes in which an air conditioner is being replaced with a heat pump, dehumidification effects should be reasonably close, provided the indoor coil of a heat pump is of similar size and depth of the air conditioner coil being replaced and the airflows and cooling capacity are similar.

“Further, using a heat pump with a staged or variable-speed compressor can improve humidity control," said Reding. “The additional stages of capacity results in longer run times in cooling mode, which will result in properly controlled humidity levels.”

Most of the humidity control issues for heat pump replacements stem from poor sizing and selection choices, said Lipscomb. For example, in cooler climates, the heating load will be much higher than the cooling load. If the heat pump is sized for the heating load, it will be oversized for cooling, so the unit will cycle on and off for very short amounts of time in cooling mode.

“This dramatically reduces the coil’s ability to get cold enough to condense water from the air,” said Lipscomb. “This is a scenario where a choice was made to size to the heating load, but more often than not, there is a tendency to use rules of thumb to size, which results in a lot of unintentional oversizing.”

Lipscomb said the best practices to avoid dehumidification problems are as follows:

- Always do a thorough Manual J load calculation. Look at cooling, heating, and dehumidification (latent) loads. Compare to equipment at the design points for cooling, heating, and dehumidification to determine if the homeowner’s needs can be met with a heat pump alone.

- If the heating load dramatically exceeds the cooling load, consider a dual fuel system that will switch over to gas furnace operation below a certain temperature. This way, the equipment can more closely match the cooling load, and dehumidification performance will be improved.

- After properly calculating loads and assessing equipment it is determined that more dehumidification is needed, a standalone dehumidifier is always an option.

“Lastly, I should mention that this isn’t really an issue in dry climates,” said Lipscomb.

Final Advice

While heat pumps can provide tremendous benefits for building occupants, it is important for contractors to educate homeowners about efficient operation and how they are different from furnaces, said Reding.

“In cold climates, contractors should calculate the portion of the heating load that will be served by the heat pump, and when backup heating will be required,” he said. “If the heat pump will not cover the bulk of the annual heating hours, homeowners should strongly consider a dual fuel heat pump to avoid reliance on electric resistance backup heating, which will result in a significant increase in electric utility costs. Many electric utilities have variable or time-of-use (TOU) rates that increase when demand on the grid is high; homeowners should be aware of their rate structure and avoid turning up their thermostat during these peak times, if possible.”

If replacing a gas furnace with a heat pump, Lipscomb believes the No. 1 consideration should be emergency heat. This is true even in climates that are considered warm, such as Texas and California, which have recently seen powerful winter storms.

“These storms can lead to power outages and leave people without heat,” said Lipscomb. “In a power outage, a gas furnace fan can be powered with a small portable generator. A very large and expensive generator would be needed to do the same with a heat pump. If it’s cold enough, no heat can be a major liability to a house or a homeowner’s life. It’s very tempting to go for 100% electrification, but people need to understand the real risks.”

As with any major purchase, Brizendine advises contractors to provide homeowners with options to help them choose the right equipment for their needs. This includes making sure they have thought through the initial cost, as well as the operating costs, of their system and that they understand any cost or comfort tradeoffs or benefits they may be getting with their options.

“Homeowners should consider both current and future energy cost possibilities, differences in operation, as well as sound tradeoffs for the system,” he said. “Newer heat pump systems offer much better performance and reliability than those from several decades ago during a similar push to heat pumps, so homeowners and contractors alike should keep an open mind and do their research.”

Heat Pump Retrofit Receives Mixed Reviews

Last year, Massachusetts State Senator William N. Brownsberger decided to replace his gas furnace with an electric heat pump, and in a recent post on his website, he admits that the results have definitely been mixed.

“We’ve been very comfortable, even on the coldest days,” said Brownsberger. “But now that we’ve been through a heating season, we can do an efficiency comparison for our heat pumps. The results are disappointing — so far the pumps have been so inefficient that the climate would be better off if we had stayed on gas heat.”

He added that his conclusion does not reflect the additional fact that mid-winter, one of the two heat pumps in his home leaked 4 pounds of refrigerant.

“Between the inefficiency and the leak, the net climate effect of our heat pump conversion has so far been about the same as putting a typical car on the road for a year,” he said.

Brownsberger expressed surprise at the way in which the climate numbers worked out.

“Both the cost and the greenhouse gas impact of a heat pump conversion depend on how efficient the pump is in moving heat. As it turned out, our heat pumps were only about 150% efficient, although they were rated 278% efficient. That means that they needed more power to run and demanded more output from the gas generating plants that add power to our grid.”

The senator did not fault the heat pump he bought or the installers, whom he said were careful and professional.

“It may be, however, that we need better rules of thumb to predict how a heat pump will perform in a particular installation,” he said.

Report Abusive Comment