The U.S. and much of the rest of the developed world are devising and implementing decarbonization policies that will transition away from using fossil fuels for space heating purposes. The reason for this shift is to reduce the carbon emissions and associated combustion-related air pollution that are produced by heating equipment.

To enforce this transition, many cities across the U.S. have proposed or enacted regulations that would ban the use of fossil fuels in new homes and buildings. In most cases, this would result in all-electric heat pumps (HPs) being installed in new construction projects rather than gas-fired heating equipment. The problem is that while current HPs work well in temperate climates such as the Pacific Northwest and much of California, their performance often declines in colder areas such as the Northeast and Upper Midwest.

Hence, the need for the Cold Climate Heat Pump (CCHP) challenge, which the Department of Energy (DOE) hopes will result in the development of new heat pump technology that will increase performance at cold temperatures; increase heating capacity at lower ambient temperatures; and offer more efficiency across a broader range of operating conditions. Six OEMs accepted the challenge and are now working alongside DOE and other stakeholders to create next-generation heat pumps that can be used in any climate.

Growing Need

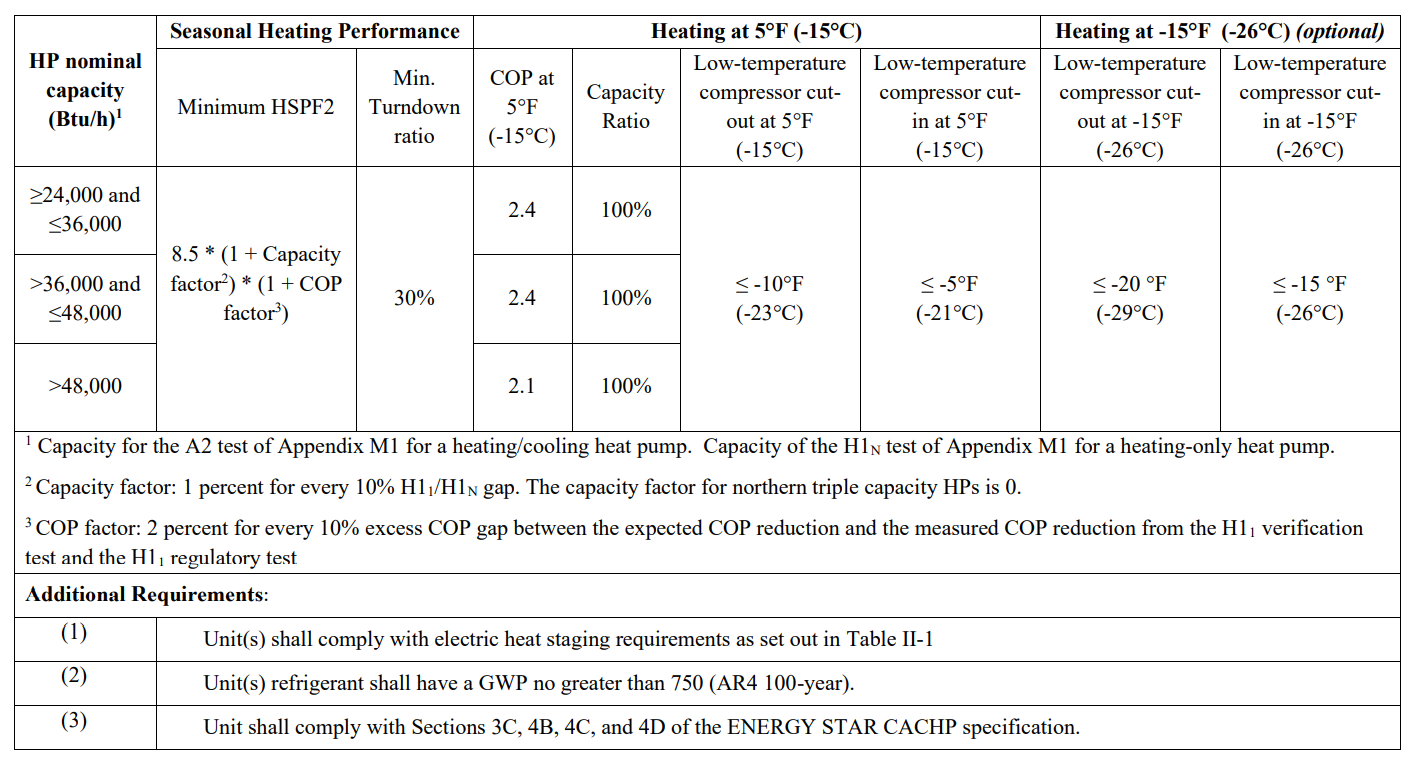

The CCHP challenge is currently focused on residential, centrally ducted, electric-only HPs and has two segments: one is for a CCHP optimized for 5°F (-15°C) operation and the other for a CCHP optimized for -15°F (-26°C) operation. The performance specifications would exceed current products on the market today and will aim to meet a 2024 commercialization timeline (see Table 1, below). The challenge also has requirements for employing low-GWP refrigerant, providing grid interactivity, and incorporating electric heat staging.

TABLE 1: Summary of challenge specifications. (Courtesy of DOE)

Click table to enlarge

OEMs like Trane Residential are excited to join the challenge, noting that the challenge addresses the industry’s commitment to reducing carbon emissions through the proliferation of sustainable HPs in places where fossil-fired equipment is used to meet the heating needs of homeowners.

“The challenge supports our overarching goals of dramatically reducing energy demands and carbon emissions and innovating with a better world in mind,” said Katie Davis, vice president of engineering and technology, residential HVAC and supply at Trane Technologies. “We boldly challenge what’s possible for a sustainable world.”

Johnson Controls agrees that the challenge presents an important opportunity to increase the adoption of heat pumps that can displace, and ultimately replace, fuel-burning and electric resistance heat sources. “CCHP technology is helping to accelerate innovation on this front and bring us one step closer to becoming a net-zero carbon economy,” said Mark Lessans, director of regulatory and environmental affairs at Johnson Controls.

While CCHPs are gaining acceptance in some regions, with support from government, industry, and utility initiatives, the DOE challenge will help address common technical and market barriers to wider adoption by consumers, which include performance at temperatures of 5°F and below, installation challenges, and electricity grid impacts during peak demand periods, said Brandon Chase, senior product marketing manager at Lennox Industries.

CCHP ROUNDTABLE: U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Secretary Jennifer Granholm and Massachusetts Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs Kathleen Theoharides listen to a presentation on cold climate heat pumps at a Boston roundtable event. (Courtesy of Mitsubishi)

“Lennox is thrilled to participate in the CCHP technology challenge,” he said. “Through participating in the challenge, Lennox is supporting its commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and tackle climate change by assisting in the development, commercialization, and adoption of next-generation CCHPs that meet consumer comfort and efficiency needs in cold climate regions of North America.”

This challenge is necessary, as more regulations will lead Americans to replace their furnaces and fuel-burning heating systems with all-electric HPs. New CCHP technology will allow them to enjoy better comfort along with greater efficiency and sustainability, said Mark Kuntz, chief executive officer of Mitsubishi Electric Trane HVAC US (METUS).

“Highly efficient, variable-capacity heat pumps, in particular, deliver the superior personal comfort experiences our society needs to galvanize public support for decarbonization and mitigate practical challenges like electric grid impacts during peak use hours,” he said. “Given the urgency of the energy transition and decarbonization, the DOE recognizes a need to support next-generation manufacturer innovations and address market barriers to encourage wider heat pump adoption by consumers. The new heat pumps will offer significant heating capacity at lower temperatures than existing models, while maintaining high efficiency.”

Ideally, the challenge will accomplish multiple goals, said Todd Nolte, senior director of product strategy and regulatory, residential HVAC, at Carrier. The first is that through collaboration with the DOE and participating OEMs, a test procedure will be developed to verify CCHP performance through lab testing.

“Second, the challenge will help accelerate the development of the next generation of heat pumps that meets consumer comfort and efficiency needs in extremely cold climates,” he said. “Heat pumps use electricity as their only fuel source, creating significant opportunities for carbon emissions reductions compared to traditional gas heating appliances. Third, through collaboration with utility and state partners, it will lead to the development of incentive programs to promote market adoption. If these goals are met, the long-term market potential is significant.”

The Technology

Creating new CCHP technology could be difficult, as the DOE challenge requires heat pumps to obtain a 2.4 COP and 100% heating capacity at 5°F. The current specification for CCHPs used by the Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships (NEEP) is 1.75 COP at 5°F, so this is a significant increase in efficiency at low ambient temperatures, said Lessans.

“When redesigning CCHPs for the DOE challenge, much of the focus will be on system optimization for compressor heating performance, in order for the new systems to be able to maintain the efficiency and capacity requirements at 5°F,” he said.

DUCTED SYSTEMS: The CCHP challenge includes only ducted heat pumps, as most homes in the U.S. have central HVAC systems with ducts that provide conditioned air throughout the home. (Courtesy of Carrier)

There are several approaches that can be taken to improve a heat pump’s performance in cold climates. These include, but are not limited to, cascade refrigeration systems, various forms of multi-stage compression, vapor injection, and liquid injection, said Jason LeRoy, director of advanced technology, residential HVAC and supply, at Trane Technologies.

“The optimal solution will consider the trade-off between customer needs, product cost, operational efficiency, reliability, and technology readiness,” he said. “It’s all about maximizing value for our customers while meeting their comfort needs.”

At METUS, the next generation of CCHPs will include advanced flash-injection and hyper-heating inverter technologies to deliver efficient, substantial heating capacity at lower temperatures than existing models, said Kuntz. Their heat pumps will also incorporate controls and connected product capabilities to mitigate peak demand challenges and expand the use of renewable energy sources. Under the challenge, CCHPs will likely have to use mildly flammable (A2L) refrigerants that have a GWP less than 750.

“The lower-GWP refrigerants under consideration have better efficiency and performance characteristics than R-410A but may require safety features like leak detection, shut-off valves, and additional ventilation,” said Eric Dubin, senior director of utilities and performance construction at METUS. “A2L refrigerants are slightly more flammable than R-410A but are less likely to ignite or sustain a flame compared to hydrocarbons. Ultimately, through product engineering, rigorous testing, and applied building science, CCHPs with lower-GWP refrigerants will contribute to a more sustainable built environment.”

Even though the goal of the DOE challenge is to create an efficient heat pump that will provide sufficient heat in very cold climates, CCHPs will still require some form of backup heating in most applications.

“This is because of the relatively smaller rated heating capacity of a heat pump compared to a furnace, as well as the inevitable reduction in heating capacity at ambient temperatures below 5°F,” said Lessans. “In the DOE challenge, program participants are required to use traditional electric resistance technology for backup heat. However, instead of electric resistance heating, CCHPs can also be integrated with a backup furnace that only runs when the heating demand exceeds the CCHP’s capacity. The combined system can result in lower source emissions, lower utility bills, and reduced electricity draw that enables improved demand response outcomes, which is critical for grid resiliency.”

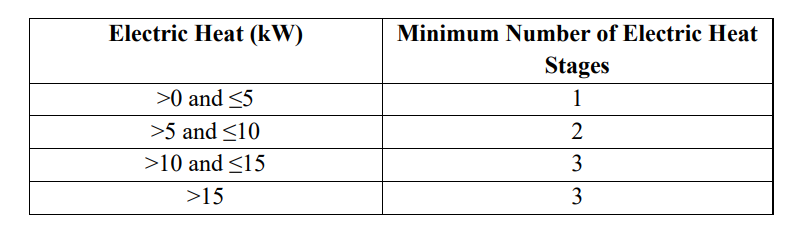

The DOE’s specifications require staged auxiliary heating (see Table 2 below), and the new CCHPs will offer significant heating capacity down to -15°F. That is why METUS expects backup heat to operate for only a few hours a year, if at all.

TABLE 2: Electric heat staging requirement. (Courtesy of DOE)

“From experience, auxiliary heat activates infrequently in homes using our current hyper-heating units, which provide heating capacity down to -13°F,” said Dubin. “The new HP systems will include controls to coordinate changeover. Electric resistance heat is a viable backup heat option, particularly in new construction, while in a retrofit, a preexisting furnace or boiler might serve as the auxiliary system.”

OEMs won’t have a lot of time to work on their CCHPs, as the DOE challenge schedule calls for the lab prototype for performance verification to occur in the early-mid 2022 timeframe, noted Davis. The field test prototype will start in the winter of 2022-2023, with the potential to continue in the 2023-2024 winter, and a final product is expected to be commercially available in 2024. “Our plan is to deliver a CCHP within the timeframe set out by the DOE’s challenge,” she said.

Other OEMs believe they will have products ready by the deadline as well, and they are embracing this unique opportunity to work together in order to achieve significant advances in HP technology. According to Chase, Lennox looks forward to working alongside other industry leaders and the DOE to advance the adoption of CCHPs by manufacturing and delivering maximum energy-efficient, high-performance heat pumps. “Together, we are confident that we can help reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, improve air quality, and help preserve our environment for future generations.”

Nolte added, “Heat pumps represent an important technology to help reduce GHGs and fight climate change, and there is further work to be done in defining adequate performance of heat pumps in cold climates, as well as advancing the overall technology. This program provides a great opportunity to partner with the DOE to begin to address these challenges. The urgency of climate change requires us to be bold, to innovate, to disrupt, and most importantly, collaborate.”

Report Abusive Comment