Under the federal American Innovation in Manufacturing (AIM) Act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been given the authority to phase down the consumption and production of high-GWP HFC refrigerants in the U.S., such as R-410A and R-404A, by 85% over the next 15 years. If not handled correctly, there is concern that the U.S. phasedown could resemble that of the European Union (EU), which has experienced a number of problems since it started phasing down HFCs (or F-Gases, as they’re called there) in 2015.

Per the 2014 EU F-Gas Regulation guidelines, production of virgin HFCs in the EU (compared to the baseline) was cut about 7% percent in 2016, but in 2018, that rose to 37%, and in 2021, 55%. Knowing that these steep drop-offs would occur, experts had hoped end users would proactively reduce their use of HFCs. But that did not happen, and prices of some HFCs skyrocketed, contractors scrambled to find refrigerant at any price, and a thriving black market for illegally imported refrigerants continues to plague the region.

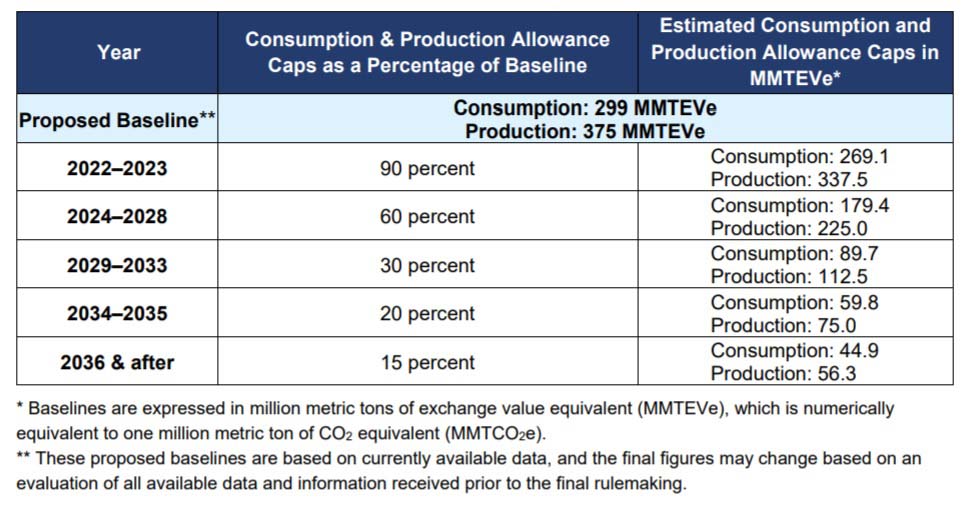

Of course, what happens in Europe may not necessarily occur here, but it’s definitely a cautionary tale. The U.S. will also have a few steep production cuts — the first one coming in 2024 (see Table 1) — but industry experts say that the country is in a better position to handle them.

Click table to enlarge

TABLE 1: HFC phasedown schedule and consumption and production allowance caps. (Courtesy of EPA)

The EU Situation

There were several issues that led to the problematic phasedown of HFCs in EU, one of them being that in the years just prior to the implementation of the F-Gas regulation, there was a significant amount of inventory that was pre-built into the system, said Brandon Marshall, North American market manager of thermal and specialized solutions at Chemours. This created a false sense of security that the market could continue to operate without beginning to transition away from high-GWP solutions.

“As a result, once the pre-built inventory was consumed, the demand of high-GWP products was still too high, and there was not enough quota to support the market,” he said. “This created an unnecessary shock to the market in the form of higher prices and insufficient availability of high-GWP HFCs that the market was still too reliant on.”

In addition, Marshall pointed out that the potential effects of the CO2-equivalent quota reductions were not fully understood, and many in the value chain were focused on the specific future years when GWP limits would be applied to service and new equipment bans. These factors combined led to minimal momentum and a slow transition to lower-GWP solutions while refrigerant was still readily available, he said.

The phasedown in the EU with F-Gas legislation was also unprecedented, said Ken West, vice president and general manager at Honeywell Fluorine Products, and the industry wasn’t as prepared as it is now. This led to the shortages in equipment for low-GWP materials and the increase in prices.

“The EU was the first mover globally in this transition, and the industry has learned lessons from that experience,” he said. “The U.S. phasedown will be more organized and more orderly than the phasedown in the EU and will provide flexibility within the industry. In the EU, we have worked with OEMs on lower-GWP solutions, and systems using these solutions are now readily available. In addition, A2Ls and retrofits in commercial refrigeration with alternatives such as R-448A are commonplace and understood.”

The issue in the U.S. is also slightly different, said West, noting that the U.S. has a large percentage of low-GWP alternatives, such as HFOs, that are manufactured within its borders and Europe does not. In addition, unlike the EU, the U.S. has the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which has a direct line to the EPA and can alert the proper authorities of illegally imported material, he said.

One of the other issues that led to dramatic price fluctuations in the EU was the lack of sector regulations, said Katie Davis, vice president of engineering, residential HVAC and supply for Trane Technologies and the Trane Residential brand. In the U.S., EPA plans to facilitate the transition to alternatives through restrictions on the main sectors that use HFCs, including refrigeration, air conditioning, aerosols, fire suppression, and foam blowing. Some of these sectors will be able to transition away from HFCs fairly quickly while others will need more time, so keeping this flexibility is key for many in the industry.

“Sector phasedown requirements should be well developed and derived in a proactive manner if the phasedown is to go smoothly,” said Davis. “Without sector regulations, the transition would follow the supply of refrigerants, which could create pinch points for virgin material. We support the development of sector regulations to provide additional certainty for new and existing equipment.”

Davis added that if other essential elements are not in place, including readiness of codes and standards (building codes), methods of containment and governance, and infrastructure to support reclaim, recycle, and reuse programs, the phasedown would be achieved through market forces and laws of supply and demand. As a result, that could result in shortages and higher prices.

U.S. Transition

Something that would help ensure a smooth HFC phasedown in the U.S. is if the EPA were to incorporate a predictable year-over-year successive phasedown, said René Molina, global business director of fluorochemicals at Arkema. That would increase awareness of the changes over time, which would help prevent last minute, abrupt reactions in the marketplace that often result in pricing spikes and product shortages.

“Additionally, any new phasedown rules should be communicated in a simple, clear manner, provide enough visibility into the future to allow for planning throughout complex supply chains, and be properly enforced,” he said. “A key consideration in a phasedown is to ensure different stakeholders, such as refrigerant producers, smaller producers, and even local authorities, adapt to the new framework at a similar pace. A system that exposes the market to opportunistic players and does not balance domestic producers and importers in an equitable manner can lead to volatility.”

To reduce volatility and avoid shortages of HFCs, EPA is working on production and allocation rules, which should be in place by October. EPA’s allocation program will define the methodology used to distribute allowances as well as determine the entities that will receive allowances. Essentially, companies or organizations will receive a set quota or allocation of refrigerant they can produce or import, then that allocation will be phased down over time.

Avoiding shortages will also require action from companies within the industry, including an increase in recovery/reclamation, refrigeration retrofits to lower-GWP alternatives, and early shift to low-GWP air conditioning where codes allow, said Karen Meyers, vice president of government affairs at Rheem Mfg. Co.

“Industry reclaim activity has been slowly growing with the focus on responsible refrigerant management,” she said. “We expect this to increase with the phasedown of high-GWP refrigerants. In addition to the proposed California regulation, which requires reclaim use, the supply and demand effects of AIM implementation should make the economics of refrigerant reclamation much more attractive.”

Still, the current supply of reclaimed R-410A is not high because the industry really didn’t start using it until 2010, so most of that equipment is still in service, said Davis. But she predicts that reclaim levels will increase as the transition evolves and companies such as Trane increase their refrigerant reclaim programs.

“We don’t currently use reclaimed refrigerant in new residential equipment, but we are supportive of reclaim and believe it is a vital part of the program to ensure no new introduction of higher-GWP HFC refrigerants,” she said. “However, at this time, there isn’t enough reclaimed R-410A available to transition new production to reclaimed refrigerant. We expect to see the industry transition to low-GWP refrigerants by 2025, which will free up reclaimed R-410A for service.”

Looking Ahead

There will be other challenges the HVACR industry will face as a result of the HFC phasedown, including the introduction of mildly flammable (A2L) alternatives that will be used in new equipment. While these refrigerants are available, they have not yet been adopted into new building codes or equipment.

“States should move promptly to adopt these new codes, including ASHRAE Standard 15, to ensure uniform standards across the country,” said Molina. “Appropriate technical training is paramount for a safe and cost effective transition to A2L refrigerants. We support ACCA and other key organizations in developing, and eventually offering, technical training courses from implementation to ongoing service operations.”

SAFE AND SUCCESSFUL: Safeguards will be added to new equipment containing A2L refrigerants, and Rheem is preparing installers and contractors with training and information needed to be safe and successful. (Courtesy of Rheem)

Many OEMs will also offer training, including Rheem, which is committed to training 250,000 plumbers, contractors, and key influencers (e.g., distributors, suppliers) on sustainable products, installations, and recycling best practices.

“Rheem is providing training and support to our contractors and distributors regarding the benefits of the new low-GWP refrigerants to demonstrate why it is the right solution for the consumer and environment,” said Meyers.

As seen with the last refrigerant transition from R-22 to R-410A, stockpiling could also become an issue for the industry. However, it’s important to keep in mind that this strategy can be counterproductive for a few reasons, said Marshall.

“First and foremost, it can provide the market with a false sense of security that transitions are not required, similar to what happened in the early years of the F-Gas regulation in Europe, leading to more severe market tightness and/or shortages when the stockpile runs out unexpectedly,” he said. “Second, stockpiling large quantities of high-GWP HFCs does not support the overall environmental goals that the EPA and industry are attempting to achieve with the regulations.”

Marshall added that if stockpiling becomes a big enough issue, a floor tax could potentially be implemented by the federal government, which would impact companies holding inventories of certain products.

“A floor tax is not currently in place, but it is something that businesses should consider when evaluating large value purchases that could have a slow inventory turn rate,” he said.

As can be seen, the HFC phasedown will bring with it numerous changes to the field of HVACR, but if those in the industry work proactively, there should be an ample supply of refrigerant available to service existing equipment.

“If everyone in the value chain, from OEMs to contractors to end users, does their part to promptly transition to lower-GWP solutions where and when possible, focus on leak reduction, and properly recover and reclaim refrigerant, we should be able to achieve an orderly phasedown as an industry,” said Marshall.

Illegal HFC Imports, Here and Abroad

The illegal smuggling of HFCs triggered by the F-Gas regulation continues to be a problem in the EU, and threatens EU climate commitments, said Ken West from Honeywell. There is a thriving black market for illegally imported HFCs, which also often involves incorrectly labeled product and the use of illegal disposable containers. It is also funding organized crime, impacting the livelihoods of business owners across the value chain, and circumventing important tax revenue for EU member states, he said.

“According to new data released this year, smugglers trafficked shipments of HFCs up to a maximum of 31 million tons CO2e across EU borders in 2019 alone,” he said. “The illegal smuggling of HFCs is made possible by the uneven enforcement by member states of the F-Gas regulation. Where fines are low, criminal organizations simply factor in the possibility of a fine as a marginal business cost.”

Brandon Marshall from Chemours agrees that the black market for HFCs in the EU is a big problem; however, he noted that there has been an extensive increase in efforts to counter illegal trade, led by the European Fluorocarbon Technical Committee (EFCTC). Through border and customs enforcement, there has been a significant increase in product seizures and fines.

In the U.S., counterfeit or illegal refrigerant is not present at the same scale as is seen in other parts of the world, but that does not mean that it is non-existent, said Marshall.

“These refrigerants can take the form of intentional mislabeling of one product for another (e.g., claiming a cylinder of R-22 when it is really filled with R-134a) and can be dangerous (e.g., filled with gas that has a different safety classification than what is shown on the cylinder),” he said. “More times than not, these issues present themselves once the system is charged and running with poor performance.”

Once the regulations are in place and the phasedown is implemented, there is the potential for counterfeit and illegally imported HFCs to increase in the U.S., said René Molina from Arkema. As a result, the U.S. will need to be watchful for counterfeit or illegally imported products and the risks they pose.

“Counterfeit products are always a concern, and the U.S. is not immune to such risks,” said Molina. “In addition to posing serious safety concerns, counterfeit products damage the environment, legitimate suppliers, and consumers. Arkema knows consumers are shopping for the best alternatives, but we always recommend they purchase HFC products from a knowledgeable and reputable supplier. We also anticipate that the EU experience will inform the EPA when issuing the final rule.”

Report Abusive Comment