Polyolesters (POEs) are a family of synthetic lubricants manufactured by reacting an alcohol with an organic acid to form a single molecule.

The manufacturing process involves the reaction of a mixture of organic acids with one or more alcohols to give the desired polyolester. The reaction is carried out at an elevated temperature and water is constantly removed. The reaction is driven to completion with virtually no acids or alcohols remaining.

There are many types and grades of esters, and it is therefore important to understand that all esters are not the same. Several important properties of esters affect their performance as lubricants.

These include lubricity, miscibility, viscosity, solubility, and moisture content.

Hygroscopicity And Moisture

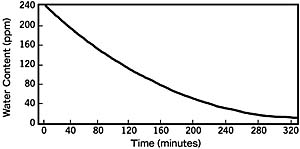

Hygroscopicity is a term used to describe a lubricant's and/or refrigerant's affinity for moisture. HFC refrigerants and POE oils have a polar molecular structure, which attracts the polar water molecule. Therefore, the solubility of water in HFCs and HCFCs is many times greater than in the CFCs they replace.POEs are also hygroscopic and can pick up more moisture from their surroundings and hold it much tighter than the previously used mineral oils. The rate that POEs pick up moisture depends on temperature, relative humidity, exposure time, and relative surface area. (See Figure 1.)

Moisture can enter the refrigeration system by a number of routes:

Measuring Moisture

Karl Fischer titration has be-come the accepted standard method for laboratory determination of moisture in refrigerants and lubricants. The technique is particularly simple when analyzing oil samples; it involves weighing the sample, introducing the sample into the titration vessel, and reading the mass of moisture in the sample.The mass is typically given by the titrator in micrograms. Dividing by the sample weight gives parts of water per million (ppm) of lubricant.

It is important that the introduction of moisture into a system is minimized and the removal of the moisture takes place effectively. At high levels of moisture, the performance of the refrigeration system may be adversely affected.

Water can interact with:

If these interactions take place, they can lead to the following losses in system performance:

POE lubricants below their moisture saturation limit (approximately less than 3,000 ppm) contain no free water; ice crystals are therefore unlikely to form.

Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis is the reverse of the esterification process, in which water reacts with ester to form the original organic acid and alcohol.The degree of hydrolysis is driven by the amount of water present. A higher moisture level will lead to a higher degree of hydrolysis. The speed at which hydrolysis occurs depends on the temperature of the system and the acid value. (Acids can act as a catalyst.) It also has been demonstrated that certain additives, high initial acid values, and impurities inside the system can catalyze this reaction.

For hydrolysis to occur, a sufficient amount of water must exist in the refrigeration system at an elevated temperature (greater than 80 degrees C). Even at relatively high moisture contents, hydrolysis is insignificant at ambient temperatures. When the water content of the system is low, hydrolysis does not occur.

If the system contains extreme moisture levels (in excess of 500 ppm) and is operating with discharge temperatures in excess of 170 degrees, the system will exhibit its own operational problems, especially within a low-temperature plant.

Is hydrolysis of ester lubricants a common occurrence? Actually, no. The concern has arisen as a result of several hydrolytic stability tests, which have been conducted in the laboratory at very high water levels (greater than 2,000 ppm) and highly elevated temperatures. That is an order of magnitude greater than expected or seen in the oil under normal operating conditions.

While there is a theoretical potential for hydrolysis in refrigeration systems, this is severely restricted by the lack of available water. It is suggested that the level of water in the system after assembly be maintained below the equivalent of 500 ppm in the lubricant, preferably below the equivalent of 100 ppm in the system. In addition, the water drying rates with suitable-capacity driers containing molecular sieve are extremely rapid even for wet systems.

How To Remove Moisture

Moisture can be removed from a refrigeration system by applying a vacuum.POEs hold moisture more tightly than mineral oil. But in the case of R-134a, the refrigerant effectively competes with the ester lubricant in partitioning the water (i.e., the water moves from the lubricant to the refrigerant).

Approximately 50 percent to 60 percent of the moisture injected into an air conditioning system remains in the refrigerant. The rest mixes with the compressor oil.

The inclusion of a drier in the refrigeration system reduces the equilibrium moisture content of both refrigerant and lubricant phase. Moisture is quickly and efficiently removed by the drier, which yields dramatic drying (pulldown) rates. (See Figure 2.)

During servicing of the refrigeration system, the use of a filter-drier with a high percentage of molecular sieve will reduce the chance of water contamination of various system components (in particular, the expansion device and evaporator).

Drier Selection

The ability to remove water from a refrigeration system is the most important function of a drier. By minimizing the free water in the system, the ability of acids to form or hydrolysis to take place is greatly reduced.Here are some of the main influences on drier selection:

Alumina may catalyze the hydrolysis of POE lubricants, creating organic acids since both water and lubricant are adsorbed into the pore openings of the alumina. However, provided the filter is not saturated, these acids may remain bound to the drier once they are formed.

Different OEMs recommend a variety of drier materials based on the above selection criteria and the oils they have approved. Several OEMs quote acceptable levels of alumina in mixed drier systems, while others recommend 100-percent alumina or 100-percent molecular-sieve driers. You need to refer to the OEM's recommendations when selecting the proper drier.

ASERCOM, the industry's global compressor organization, recommends the minimum of 70-percent molecular sieve and a maximum of 30-percent activated alumina for liquid-line driers.

Handling POEs

Good housekeeping practices should eliminate most potential sources of moisture. These include:This material was jointly prepared by Virginia KMP and Uniqema. For more information, visit www.virginiakmp.com and www.uniqema.com/lubricants/index.htm.

Publication date: 02/02/2004