California is committed to phasing down the use of HFCs, and its timeline to do so is rather aggressive. That’s because the state legislature recently passed the California Cooling Act (Senate Bill 1013), which requires the state to reduce HFC emissions by 40 percent below 2013 levels by 2030.

To meet this mandate, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) has proposed a GWP limit of 150 for new stationary refrigeration systems containing more than 50 pounds of refrigerant, as well as a ban on sales of virgin refrigerants with a GWP above 1,500, starting on January 1, 2022. In addition, CARB is proposing a GWP limit of 750 for all new stationary air conditioning systems (residential and commercial) starting January 1, 2023, and the same GWP limit for new chillers, effective January 1, 2024.

The short timeline to implement these changes will be tough to achieve, and at CARB’s recent stakeholders’ meeting in Sacramento, California, manufacturers and end users expressed concern about the feasibility and cost of implementing these regulations.

PROPOSED REFRIGERATION RULES

Richie Kaur, Ph.D., an air pollution specialist at CARB, discussed the regulatory impacts for stationary refrigeration, including an overview of the costs associated with installing new equipment that utilizes <150 GWP refrigerant. She clarified that this proposal does not require the replacement of existing equipment by a certain date; however, new facilities — and those replacing a majority of their equipment — will be required to install units that utilize <150 GWP refrigerant starting in 2022.

Kaur noted that for all system sizes, including supermarkets, grocery stores, and cold storage warehouses, there are <150 GWP options currently available in the market. In fact, as of 2018, more than 100 supermarkets in California are already using low-GWP refrigerants such as ammonia, CO2, and hydrocarbons.

“Since there is more than one option available for each system size, we believe the 2022 date will work for this proposal,” she said.

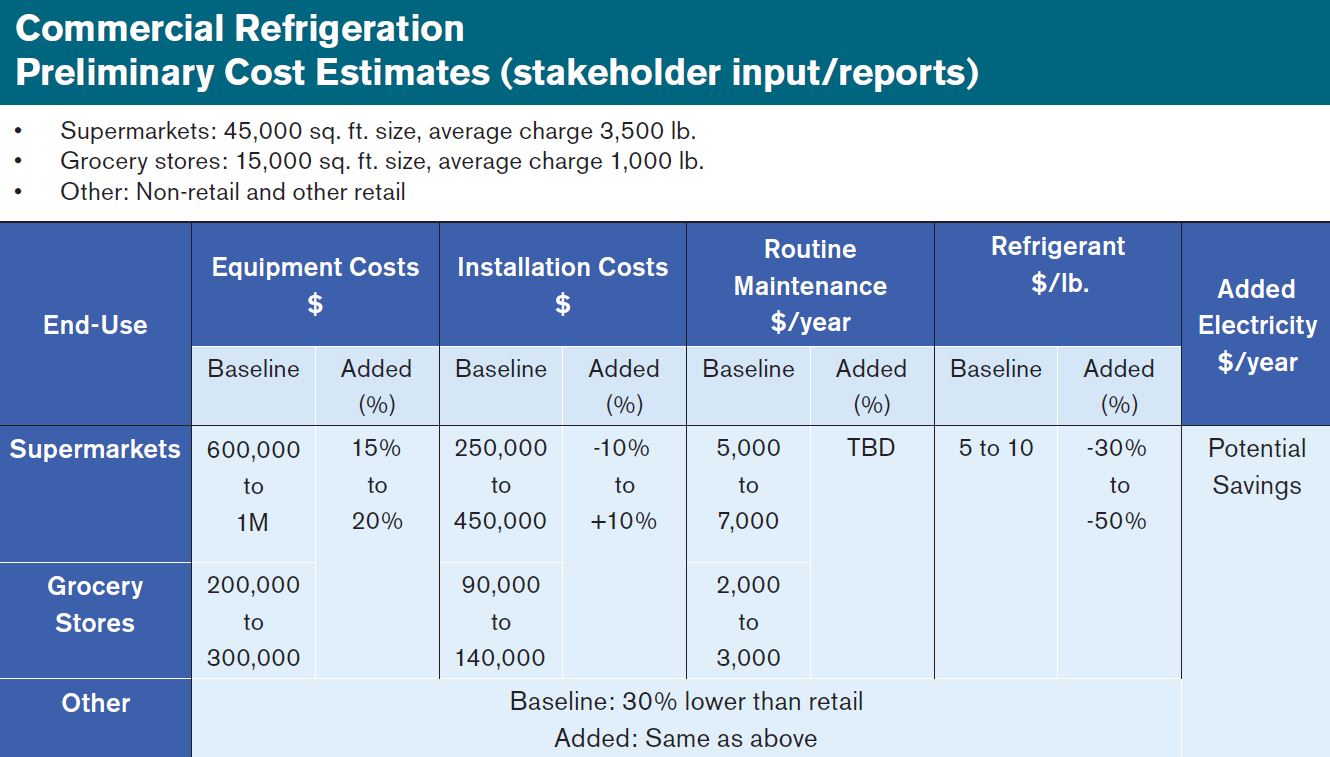

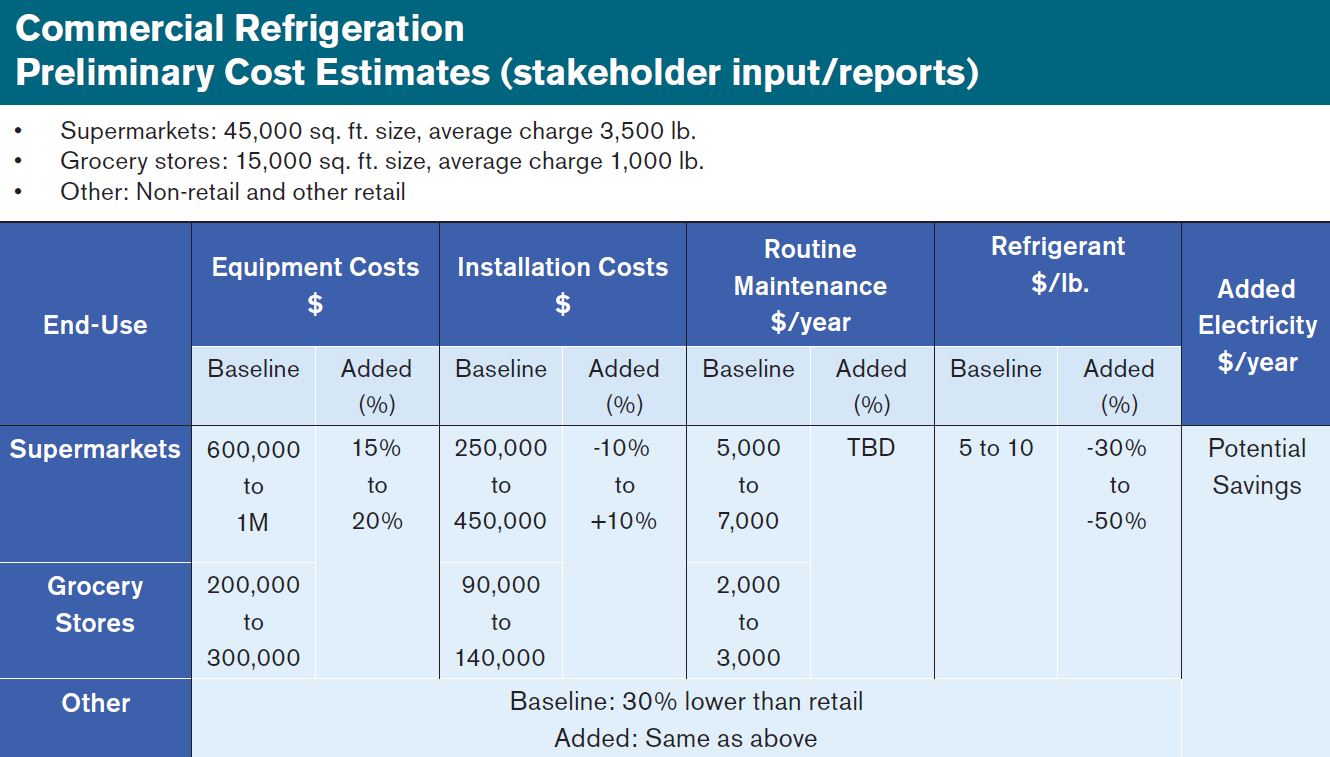

That said, the transition to <150 GWP refrigerants will likely be costly. In coming up with its economic impact analysis, CARB took into consideration the baseline cost of a traditional direct expansion centralized system that utilizes R-407C or R-404A and compared it to a system that utilizes a <150 GWP alternative. This included first cost as well as installation, maintenance, electricity, and refrigerant costs.

As seen in Table 1, for both supermarkets and grocery stores, the first cost for a low-GWP system would be about 15 to 20 percent higher than a traditional system. Installation costs typically range between 40 and 50 percent of the cost of the equipment, and for low-GWP systems, these costs can be somewhat higher or lower.

Click table to expand

TABLE 1: CARB’s preliminary cost estimates for commercial refrigeration systems.

TABLE 1: CARB’s preliminary cost estimates for commercial refrigeration systems.

“The installation cost for low-GWP systems can actually be lower, because those cases come electrically prewired, and there’s thinner copper piping,” said Kaur. “But in some cases it’s higher, so we estimate that the added cost range for installation is between -10 and +10 percent for low-GWP systems.”

For routine maintenance, CARB’s baseline cost includes about four to six hours of labor per month, or about $5,000 to $7,000/year for a supermarket. However, Kaur noted that more information is needed about the maintenance required for low-GWP equipment before this estimate can be completed.

Refrigerant savings can be significant with low-GWP systems. The baseline cost for R-407C is between $5 and $10/pound, and because most of the current low-GWP solutions use inexpensive natural refrigerants, CARB estimates the difference in cost would be -30 to -50 percent. Electricity is more difficult to quantify, because savings depend heavily on how those systems are optimized and maintained. CARB is looking for more concrete data in this area.

Kaur then asked meeting attendees for input regarding the feasibility of using low-GWP systems in new and existing facilities. There was an extensive discussion regarding CARB’s definition of new refrigeration equipment, which includes equipment that is first installed using new or used components, as well as any refrigeration equipment that is modified such that the capital cost of replacing or cumulatively replacing components exceeds 50 percent of the capital cost of replacing the entire refrigeration system.

Several supermarket operators in attendance said that determining what constitutes 50 percent of the capital cost would be almost impossible to calculate, particularly in older stores. In addition, refrigerated cases and fixtures on the floor are changed more often than centralized rack systems, so there were questions as to how those replacements would count toward the 50 percent threshold.

In response, Kaur noted that it will be necessary to clarify whether the regulation applies to new construction or replacement. She said the intent of the proposal is to regulate all equipment, whether it’s going into new or existing stores, but perhaps a different performance standard is needed for existing stores. However, almost 40 percent of existing stores are still using R-22, so the goal of the regulation is to get those stores to move to the lowest possible GWP refrigerant as quickly as possible.

One of the OEMs asked why the focus was only on transitioning to low-GWP refrigerants, rather than reducing leak rates. He contended that smaller systems that contain less than 300 pounds of refrigerant should be allowed a higher GWP limit, because they have much lower leak rates than larger systems.

The conversation eventually veered back around to cost, with attendees expressing concern that low-GWP systems may be too expensive, particularly for mom-and-pop stores.

One grocery store operator summed up the discussion by saying, “We’ve having two separate conversations here. One is the possibility of future drop-in refrigerants that we would use in existing systems that would meet the low-GWP definition and whether that’s feasible. Today, it’s not, because the safety standards don’t exist, and the technologies don’t exist. The other conversation is whether or not it’s possible — or feasible — to take the low-GWP technologies that are out there today and put them into an existing store as a replacement. Is it possible? Yes. Is it economically feasible? Probably not today, and that’s the biggest challenge. There’s no systematic approach in most grocery stores to replacing cabinets and cases — you may have a case that’s 15 years old on the sales floor and one that’s six months old. And if you have to replace all of those, you’re going to have a significant economic impact.”

PROPOSED A/C RULES

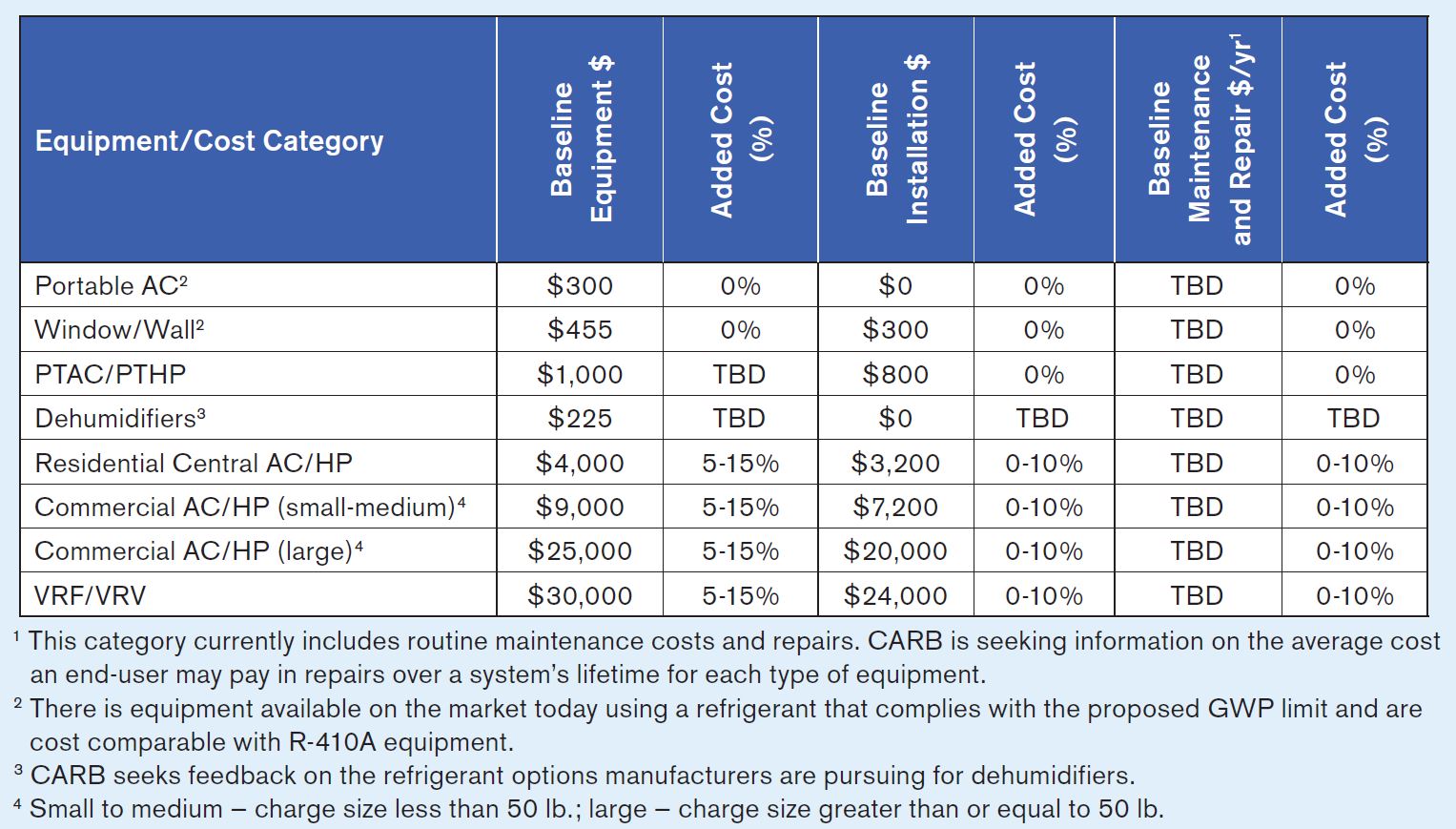

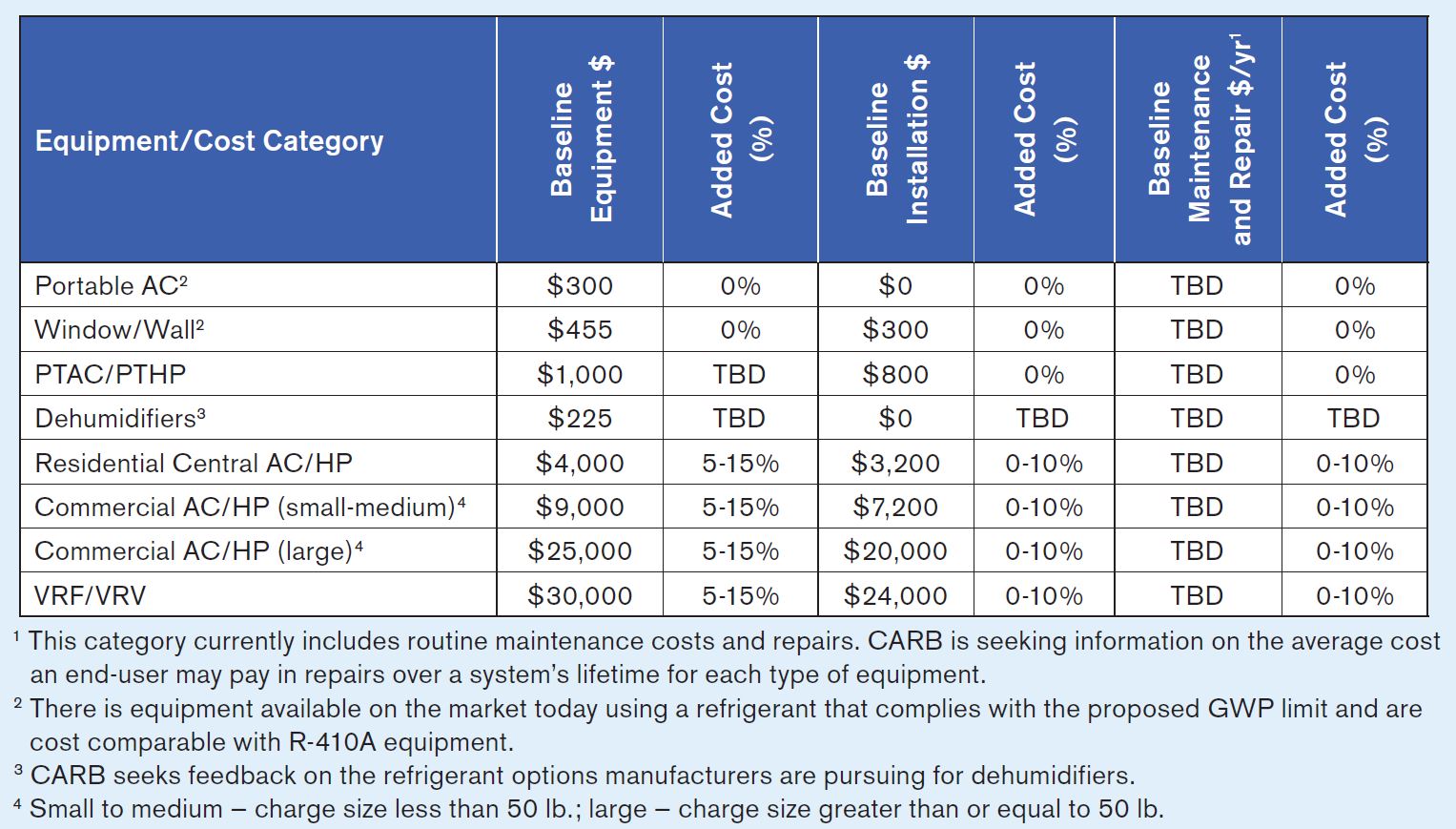

Following the refrigeration discussion, Kathryn Kynett, an air pollution specialist at CARB, outlined the proposed GWP limit for new stationary air conditioning equipment. She noted that the regulation is still in its early phases, which is why CARB is looking for input from stakeholders regarding additional costs for systems using <750 GWP refrigerant when compared to the baseline costs of a traditional HVAC system. (See Table 2.)

Click table to expand

TABLE 2: CARB’s preliminary cost estimates for low-GWP air conditioning systems.

TABLE 2: CARB’s preliminary cost estimates for low-GWP air conditioning systems.

For residential air conditioning systems (typically under 5 tons), including packaged and split ducted systems as well as ductless systems, CARB estimates that a <750 GWP system will cost 5 to 15 percent more than a traditional system. Kynett noted that the added costs of maintenance, repair, and refrigerant for <750 GWP systems are still unknown, so more data is needed in this area.

Kynett added that more information is also needed regarding the types of residential equipment and components that are currently coming into California. She said that while some systems will be used in homes that are installing a/c for the first time, replacement components are also part of the equation.

“Our intent is to allow people to make repairs, so we need to know how many shipments involve a single component replacement,” she said. “We also want to make sure that our regulatory text doesn’t create loopholes, so that homeowners can piecemeal a system together by buying one component at a time until they have a whole new system, and they’ve gotten around the requirement to be more climate friendly. We’re looking for a way to define new equipment, repairs, and components in the most sensible way to allow people to have air conditioning in California.”

For commercial air conditioning systems, CARB again estimates that the additional cost for a <750 GWP system will be in the range of 5 to 15 percent, but there are still many unknowns. Kynett said that they are particularly interested in learning more about VRF systems, including how much more energy efficient these systems are, as well as how much they typically leak.

During the open discussion, one of the OEMs expressed concern about the hard cutoff date of 2023, noting that a phaseout over three to five years would be better.

“This is a very, very large industry that does not change directions quickly overnight,” he said. “Especially on the commercial side, we still have many questions that are unanswered on codes. Those will get resolved, but it leaves us very little time for transition. The industry has experience making these changes, but we had about 14 years to make the transition to R-410A, and we may only have one or two years, if that, if we have a cutoff in 2023. If you have a phaseout with an escalating economic incentive for the recycling of HFCs, I think you will get a much better, more orderly transition. A 2023 hard cutoff will be very difficult and very painful. I urge you to look very carefully at that.”

Given that the air conditioning sector contributes such a large portion of the state’s HFC emissions, Glenn Gallagher, an air pollution specialist at CARB, said that moving the cutoff date would not allow the state to reach its goal of a 40 percent reduction by 2030.

“I’ve looked at a lot of different start dates for a lower GWP refrigerant requirement, and with a delay of one year, we just can’t come even close to our 2030 reduction targets,” he said. “Now, if we had a 2050 target, that’s a different story, but we have a hard 2030 target.”

The next steps for both the refrigeration and air conditioning proposals involve gathering more input from stakeholders, then scheduling a second workshop later this fall. The final regulation recommendations will be presented at the CARB board meeting in May 2020.

See more articles from this issue here!

Report Abusive Comment