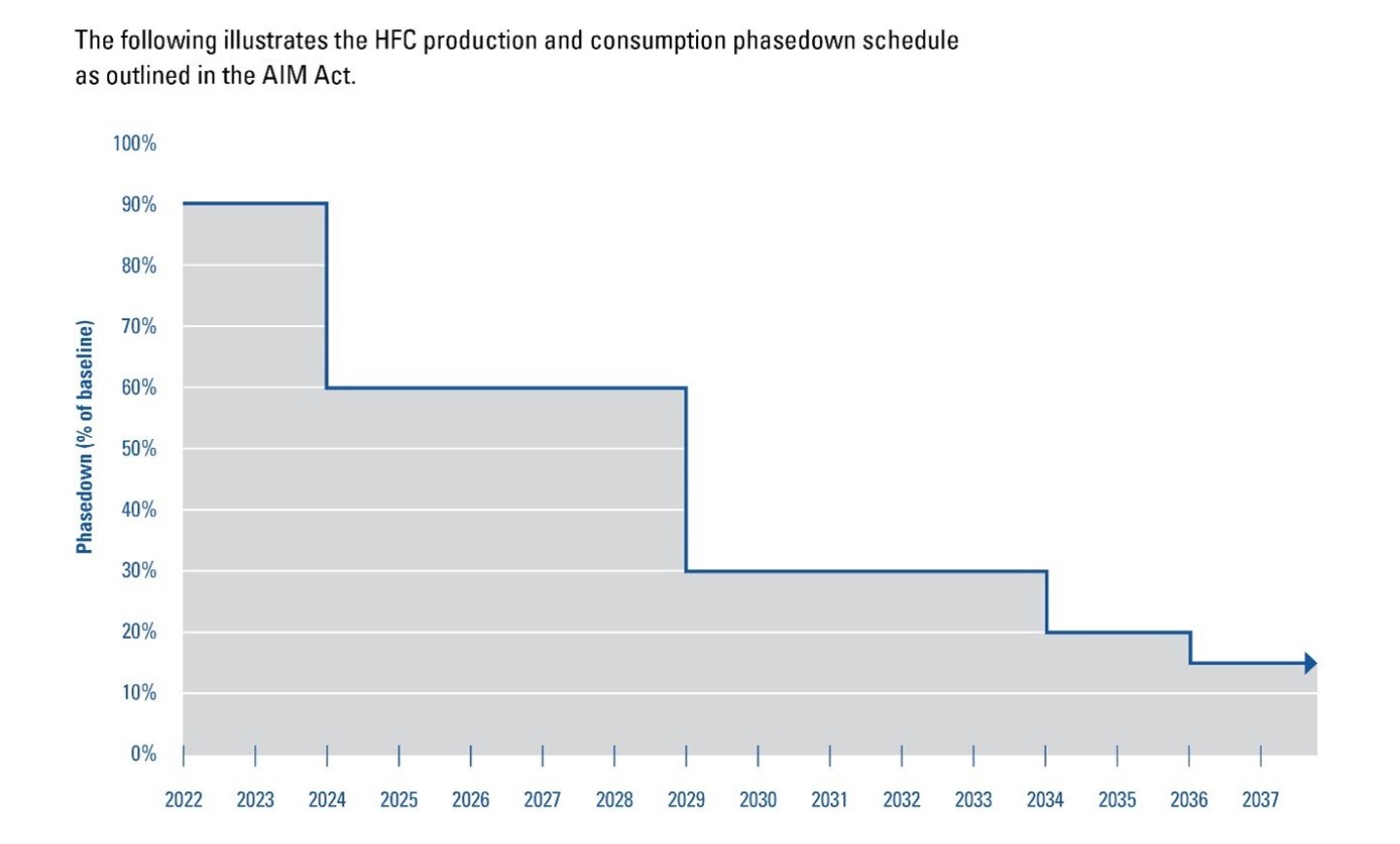

In December 2020, Congress passed the American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act, which gave the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to phase down HFCs to 15% of their baseline levels by 2036. It was up to the EPA to decide how to implement the legislation.

In September 2021, the organization delivered its final rule, which established the HFC baseline, as well as the phasedown schedule, and an initial methodology for issuing allowances for 2022 and 2023. Further guidance came in October 2021, when EPA released the 2022 allowances for companies that produced and/or imported HFCs in the U.S.

As part of the ongoing rulemaking process, EPA recently held a public workshop to explain how it will build off that 2021 rulemaking to establish the allowance allocation methodology for 2024 and beyond. Stakeholders were also invited to weigh in on the HFC allowance allocation methodology for future years.

HFC Allocations

In introducing the workshop, Chris Grundler, director of atmospheric programs at the EPA, noted that the first HFC allocation and trading program deliberately only covered the first two years. That’s because Congress gave EPA only 273 days to propose and finalize the first allocation and trading program, so he said there was not a lot of time to think through the different options on how to go about implementing it.

“But we promised everyone that for the next rule, which we're kicking off [at this workshop], that we're going to revisit and rethink our approach,” he said. “We’re asking a bunch of questions, and we hope to get stakeholders to think about different ways that we could do this.”

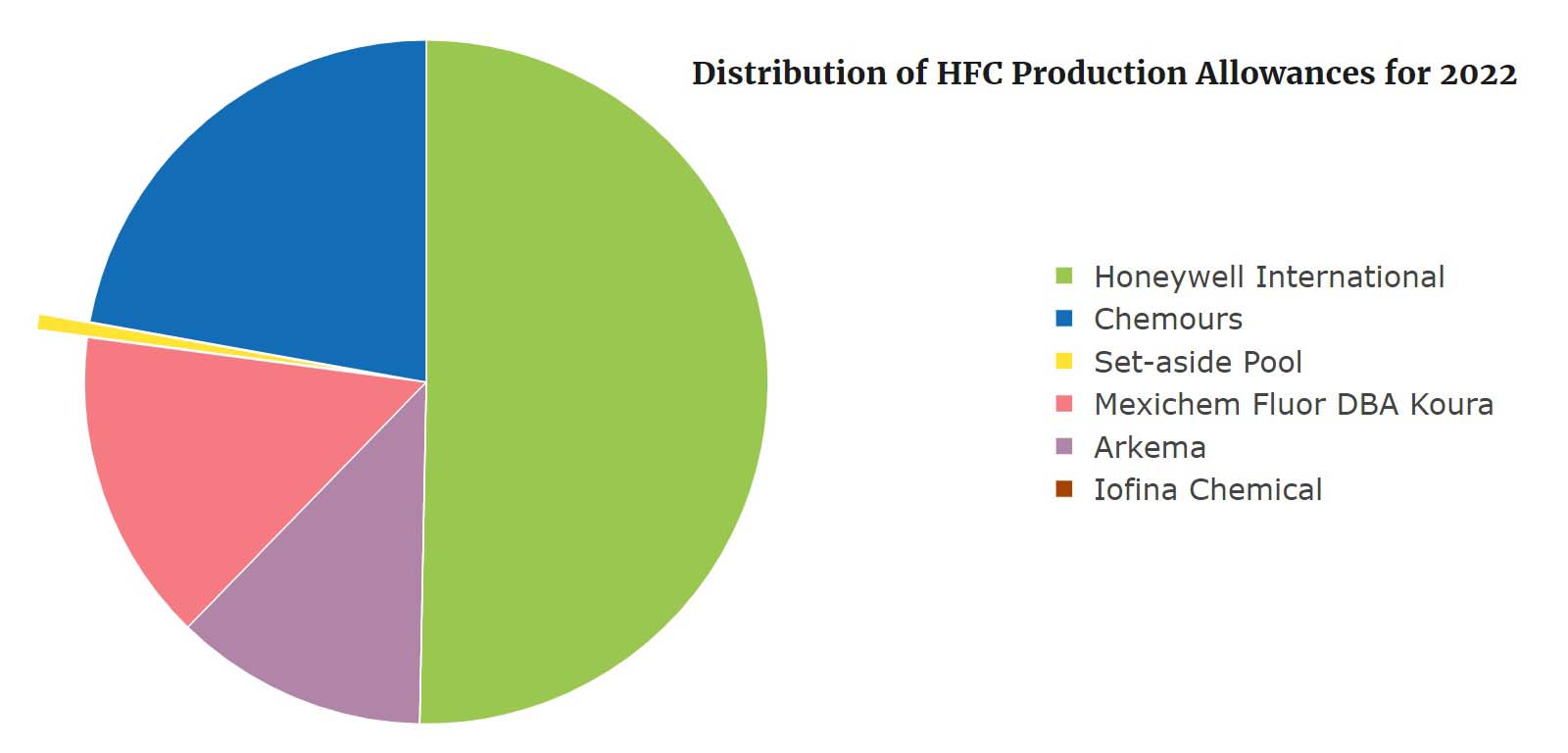

In coming up with the HFC allocation methodology for 2022 and 2023, EPA used past production and consumption data from a set number of years and based the allocation going forward on that quantity. To that end, allowances were given to companies that produced and/or imported HFCs in 2020, based on the three highest nonconsecutive years of production or import between 2011 and 2019.

Click chart to enlarge

PHASEDOWN SCHEDULE: The HFC production and consumption phasedown schedule as outlined in the AIM Act. (Courtesy of EPA)

Keeping that general pool allocation methodology for 2024 and later years is one option that EPA is considering. Under that scenario, the share of allowances that companies have now would be the same as in the next set of allocations. Luke Hall-Jordan, chief of the stratospheric program implementation branch at EPA, asked whether that approach would pose any challenges or create any advantages. There are other methodologies to consider as well.

“Maybe we want to reevaluate company allocations, to use more recent years’ worth of data,” he said. “For example, should we update the basis for issuing each company's allowances — basically, what share of allowances each company would get? We could propose using 2022 through 2024 production and consumption values, and use that to determine the share of allowances that people would get in 2026 through 2029, or other some other combination of years. But the approach would involve updating based on more recent activity.”

Click chart to enlarge

PRODUCTION ALLOWANCES: Production allowances allocated to each company for 2022. (Courtesy of EPA)

Consideration also needs to be given for how EPA would account for transfers between allowance holders, said Hall-Jordan.

“If somebody transfers an allowance in one year, and we’re using that year as a basis for future allocation, does that transfer allowance become the basis for somebody else's allowances or the person who transferred it?”

Hall-Jordan noted that one or both of these two approaches could be used for future allocations, along with an added fee for production or import. The concept behind the fee is to recognize that companies make decisions about how many allowances they need in a given year, he said. A fee would help potentially rightsize or “true up” some of that process, so that companies acquire the number of allowances they actually expect to need in a given year.

Another approach considered by EPA is an allowance auction, where companies would bid on how many allowances they would want in a given year or set of years. That number would then be the basis for determining allowances. Finally, a hybrid approach could be taken with several of these alternative methods and then transitioned in over time.

Whatever methodology is ultimately decided upon, the next allocation rule will likely last longer than the current two-year rule. But this, too, requires further thought and deliberation. As Hall-Jordan pointed out, should the next allocation rule coincide with the large production cut of HFCs in 2029? Or should there be steps in between, recognizing that there can be a fair amount of change and adjustment that happens when reducing the amount of HFC production and import in a step down? Should allowances then be adjusted at the same time?

Discussion

In the ensuing discussion, stakeholders brought up some interesting questions and concerns.

Regarding the proposed allowance auction, one participant said that this methodology would not take into account the large investment that manufacturers and packagers have already made in the industry. She said that an importer or someone new could theoretically come in and outbid a manufacturer of HFCs, because they have lower overhead. As a result, that manufacturer could end up closing its plant in the U.S., because it doesn’t have production and consumption allowances. That would be “disastrous” for the U.S., given the number of HFC-producing plants that are here, she said.

This participant also addressed allocation transfers, noting that allocation holders have the option to either import or to transfer some of their allotted quota to a domestic manufacturer to produce this material needed for their customers.

“Taking the transfers away from me if I choose to transfer them to a domestic producer incentivizes me to import rather than to use a domestic manufacturer to fulfill the needs of my customer base,” she said. “I don't think that's the objective of the AIM Act, which was designed to improve our climate and also to support our domestic manufacturers.”

Hall-Jordan said the participant raised some very valid points, particularly concerning transfers. “The transfers piece is actually an important one that we've been trying to think through as we sort of scope out these options.”

Another question involved whether EPA would be taking steps to ensure that refrigerant manufacturers used at least some of their allocations to continue producing high-GWP products such as R-404A for existing commercial refrigeration applications, rather than transitioning completely to more expensive — but lower-GWP — refrigerants such as R-448A and R-449A.

In response, Cindy Newberg, director of the stratospheric protection division at EPA, said that the agency would be taking a relatively hands-off approach. She said those decisions were best left to the industry to decide which products they want to continue manufacturing. She added that demand is going to be a big part of their decision-making process and that EPA believes strongly that companies will continue to produce a variety of products throughout the transition.

“I can't say enough how important reclamation will be in a smooth transition,” she said. “It was important for the smooth transition for ozone-depleting substances, and reclamation is what's going to help smooth the transition here, too. So even if a company decides not to make R-404A anymore, that doesn't mean it won't be available on the reclaim market.”

Another participant, Helen Walter-Terrinoni, vice president of regulatory affairs at AHRI, pointed out that HFCs used in the past won't be the HFCs that are used in the future, so perhaps it was necessary to look at them differently.

“Should we be thinking about the mismatch between the sector-based controls and the allocation? Should the chemicals be phased down in a different way?” she asked. “I don't think there's anything in the AIM Act that says you can't look at them differently from one another. And as the uses become unnecessary because of the sector-based controls coming into play, maybe that's something to think about.”

In addition, some sectors are experiencing tremendous growth, such as semiconductors. Heat pump use is also growing rapidly, which will drive the need for even more heat transfer fluids, said Walter-Terrinoni. This will become even more important in 2024, when many countries in Europe and Asia, under the Kigali Amendment, are to freeze HFC consumption levels.

“These are places where products are manufactured and shipped around the world, which means there’s going to be competition globally for access to HFCs,” she said.

Newberg responded that EPA agrees that the past is not the future, as HFCs are different chemicals than those phased out previously.

“We do think the world is changing, and we do see there's a number of differences today than there were previously,” she said. “HFCs are more often blended, and those blends are what we're seeing on the market. That is a very different world than the ODS world where blends were a rarity.”

She added that the conversation about these topics will continue, as the workshop was just the start of the rulemaking process. She said EPA looks forward to engaging with many different people in future discussions about the HFC phasedown.

This is the first of many meetings EPA plans to hold regarding the next HFC allocation rule, which must be issued by October 1, 2023. For more information, visit www.epa.gov/climate-hfcs-reduction/final-rule-phasedown-hydrofluorocarbons-establishing-allowance-allocation.

Report Abusive Comment