Forty minutes northwest of Chicago, a new fitness facility transformed what could have been commodity ductwork into a captivating “diamond.” The owners of IT Gym in Hoffman Estates wanted to add a unique look at the fitness facility, a visual focal point that would echo their customized training regimens. They fabricated the network of HVAC vents and returns from copper, an unconventional choice that not only helped set the interiors apart from other gyms but also illustrated the formability of copper sheet and coil.

(Courtesy of Nicholson & Galloway)

(Courtesy of Nicholson & Galloway)Halfway across the country, another project also chose copper, but for entirely different reasons. The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, located at 112th St. and Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan, had long struggled to protect elements of its structure from water damage. The roof above its Guastavino dome proved particularly challenging. Previous attempts to use membrane roofing had failed, so ENNEAD Architects and contractor Nicholson & Galloway chose to replace it with copper, due to its resilience, formability, and natural patination, complementing adjacent roofs and complementing the masonry walls.

Each of these projects shows benefits of working with copper materials, offering good examples of the principles that design and construction professionals should apply when using it. In fact, they represent some of the best work completed across the U.S. and Canada in recent years, earning each team recognition with a North American Copper in Architecture (NACIA) award. Their outstanding vision, expertise, and execution all started with a solid understanding of copper’s properties in building applications. This article covers some of the key points in order to raise the industry’s level of understanding on how to work with architectural copper.

Dimensions

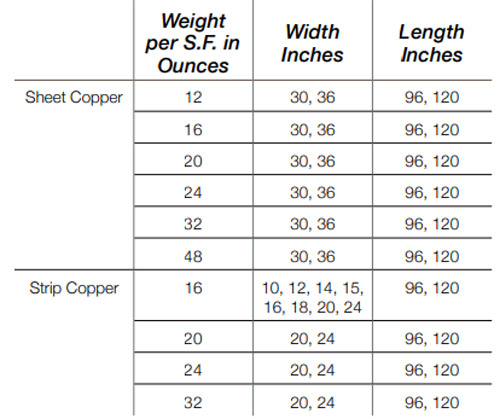

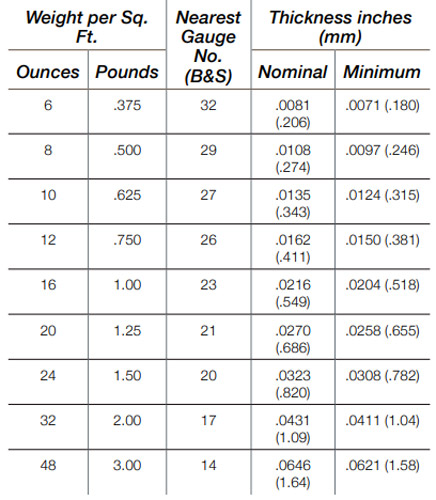

In building construction, copper is generally used in sheet and strip forms. Copper strip is 24 inches or less in width, while copper sheet is over 24 inches in width. The adjacent table shows the standard dimensions of sheet and strip copper. The thickness of sheet and strip copper is measured by its weight in ounces per square foot. For example, the thickness of 12-ounce copper is such that each square foot weighs 12 ounces. Thicknesses commonly used in construction fall between 8 and 32 ounces. The second table shows how to convert weight and gauge measurements.

Typical Dimensions, above, and weigh to gauge conversion, below. (Courtesy of CDA)

Typical Dimensions, above, and weigh to gauge conversion, below. (Courtesy of CDA)

Structural Considerations

Structural considerations play an important role in the proper design of copper applications. They affect the spacing of attachments, the location and design of joints and seams, and the configuration of other joints. The requirements may be calculated with the same formulas used in the structural analysis of other materials, such as steel and wood. Thermal effects represent a primary focus. Designs and installations must accommodate movement and stresses related to temperature variations. To do this, one can either prevent movement and resist cumulative stresses within the copper or allow movement at predetermined locations. Note that the yield strength of copper is the same for compression as it is for tension. Since buckling is likely to occur when relatively thin sections of sheet copper are in compression, sections should be designed to resist compressive loads. On St. John the Divine, contractors Nicholson and Galloway skillfully incorporated transverse seams within the dome roofing panels and strategically spaced expansion joints on low-slope, flat-seam soldered panels on the dome’s ledges, both proven methods to accommodate thermal movement.

(Courtesy of Nicholson & Galloway)

(Courtesy of Nicholson & Galloway)Patination

In the presence of moisture, salt and atmospheric borne chemicals like sulfur, copper quickly begins to oxidize and progress through the weathering cycle. Its high resistance to corrosion is due to its ability to react to its environment and attain a finish equilibrium. The oxidation process that gives copper its characteristic brown or green patinas is a result of exposure to the atmosphere. Copper turns green, for example, when appropriate acidic moisture comes in contact with exposed surfaces. The acid reacts with the copper and forms copper sulfate that adheres tightly to the surface, forming a patina that eventually covers it to protect against further weathering. These factors were important for the cathedral not only to handle the conditions of the urban environment, but also so the new elements will eventually match the patination of existing copper systems on the cathedral.

(Courtesy of Nicholson & Galloway)

(Courtesy of Nicholson & Galloway) Cost Effectiveness

When evaluating the cost of building components like roofing, flashing, gutters, and downspouts, design and construction teams must consider their performance, maintenance, and service life. Many applications of copper involve uses that are critical in maintaining integrity of the building envelope. Copper performs these functions for a long time, and copper components typically offer extremely low maintenance and long life, even in coastal and industrial environments. Copper is therefore an economical material for these and many other applications. This factor proves less important for small installations like the gym, where aesthetics is a primary consideration. For the cathedral, however, the durability of copper was an important factor, given the importance of the structure and relative difficulty of any repairs that might be required on an area located so far above the street.

Forming

Numerous methods can be used to form copper for various building systems. The following list provides brief descriptions of each method:

- Bending/Brake Forming: Mechanical forming performed with the aid of rollers, bending shoes and mandrels. Used to produce curved sections from straight lengths of tube, rod, or extruded shapes.

- Castings: Produced by pouring molten metal into a mold and allowing it to cool and solidify. Only specially formulated alloys C80000 through C99999 can be cast.

- Explosive Forming: A high energy rate forming method by which shapes are produced using a single die and energy supplied by chemical explosives. Allows formation of large shapes without heavy equipment.

- Extrusion: Forcing heated metal through an appropriately shaped die. In general, cross-section diagonals should not exceed six inches. The average thickness of copper alloy extrusions should be about 1/8 inch.

- Cold Forging: Shaping by repeated hammering at room temperature.

- Hot Forging: Pressing a heated slug or blank cut from wrought material into a closed cell impression die.

- Hydroforming: Pressing sheet alloy between a male die and a rubber piece subjected to hydraulic pressure.

- Laminating: Bonding of sheet or strip alloys to various substrates such as steel, plywood, aluminum, or rigid insulating material, usually using adhesives. The resulting panel can be quite strong, even with thin copper material.

- Roll Forming: Making shapes from sheet or strip material by passing it between multiple contoured rolls. Generally, produces softer corners than those achieved by extrusion.

- Spinning: Shaping sheet or strip alloy under pressure applied by a smooth hand tool or roller while the material is revolved rapidly.

- Stamping: Shaping sheet or strip alloy by means of a die in a press or power hammer.

(Courtesy of Kevin Ryan)

(Courtesy of Kevin Ryan)The expertise required to complete both IT Gym and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine show how important it is to have a strong understanding of copper’s physical properties when designing building elements. They also demonstrate the expert manufacturing and installation techniques that earned each team a 2023 NACIA award. They are truly excellent examples of how experienced architects and installers can create distinctive, long-lasting solutions using copper's unique properties.

Report Abusive Comment