Al

Ciuffreda

The manufacturers’ perception is that HVAC contractors will position the various products and price them like any other retail business. While this is not an unrealistic expectation on the manufacturers’ part, it is not the typical reality for most HVAC contractors.

Most retailers, like department stores or even auto manufacturers, will adjust their prices based on many factors. They may even conduct market surveys to determine the consumer’s needs versus their wants, preferences, population mix, and even geographic area. Some retailers may not even venture into a geographic area until a certain population and income level is in existence, like Olive Garden or Nordstrom’s. However, once in the market they will evaluate their products, position them, and price them accordingly.

Recently I went shopping for a new toaster. I noticed that the store offered a two-slice toaster at $23, a four-slice toaster at $39, another four-slice toaster with more knobs, a better paint job, and a chrome top for $59, and even one with LED readout for $100 (out of the question). Now do you really think a couple of knobs and a little chrome is worth $20 more for the four-slice toaster? But guess which one was sold out? That’s right, the $59 toaster was sold out. So I asked the clerk, “When do you expect the stock to be replenished?” His answer, “We get them in once a month and those are sold out in a couple of days. In fact, it is our best seller.”

Let’s look closer at the pricing between the two four-slice toasters: $20 is not a lot of money but I would guess the stores cost difference is probably less than $5, yet they get $20 more or over 35 percent just because it is perceived and positioned as a better product.

Figure 1.

PRICING THE PRODUCT

So enough about toasters, let us get back to our industry. Manufacturers assume that HVAC contractors, as retailers should, are pricing their products with the same mentality. Manufacturers have produced higher-efficient products for over 40 years and still about 80 percent of all sales are at the low end of SEER and less than 20 percent are higher SEER. Shouldn’t they be frustrated that all their efforts have not increased the share of higher SEER products? Do you think, just maybe, their perception might be in error?Now I would not deny that contractors adjust their prices somewhat, but experience has shown that most do not adjust the prices between low SEER and higher SEER with a 35 percent increase from one SEER to the next. They probably should, but they typically don’t.

Many contractors price their 13 SEER to their prospect and may quote a 14 or 16 SEER based only on the equipment price difference. Their reasoning is that everything else costs the same so they should only add the difference to the 13 SEER price. So let us see what happens with this simplistic approach.

Figure 2.

Consider that 10 percent of $5,000 is $500 and he now makes $500 on a $5,900 sale, or he only realizes 8.5 percent profit. So percentage-wise, he has made less profit. To further compound the issue, if he shifted the majority of his business to 16 SEER and maintained the same pricing strategy, he would probably move to an even higher tax bracket and make even less money. So how much should he add to retain his 10 percent profit?

To demonstrate a simplistic answer to this question, he should add $1,000 to his $5,000 for a new price of $6,000 and 10 percent of $6,000 would earn him $600 profit before taxes. However, the answer to this question is far more complicated than the simplistic approach above. The real answer is that he should refigure the price based on the higher product cost using his overhead, labor, and profit, a somewhat difficult task when sitting right in front of the prospect. Perhaps this fact alone is an argument for flat-rate equipment and installation pricing.

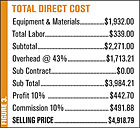

Figure 3.

To get to the actual selling price we need to add these together, obtaining Total Direct Cost (Figure 3). Then we must include the overhead (say 43 percent of the selling price), profit (say 10 percent of the selling price) and sales commission (say 10 percent of the selling price). Figure 5 uses the above percentages to determine the actual selling price.

This is how the $5,000 selling price for the 13 SEER systems was calculated. Now let us use the same format to calculate the actual selling price for the 16 SEER with the additional $900 product costs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Figure 2 demonstrates the labor costs and as assumed by most contractors should be the same, i.e., same number of people, hours, and labor costs. Admittedly, the 16 SEER might require some additional time to set “dip switches” or properly set up the thermostat to provide the additional features of the product. However, for simplicity, let’s say it is the same.

Now let us combine these figures to determine what our actual selling price should be for the 16 SEER products using the same assumptions (percent) for overhead, profit and commission (Figure 5). So the real selling price, if all costs, overhead, profit, and commissions are to be captured, should be $7,000 not $6,000. The almost $1,000 difference is due to the fact that we must recover overhead, profit, and commission on the selling price, not the additional costs. This is why the job should be repriced and not simply use the add-in equipment differentials.

Figure 5.

I must add here that many contractors have told me that the reason 80 percent of product sales are low SEER is because of new construction. Research has indicated that new construction sales might account for about 6-8 percent of total unitary sales and 6 percent would still dictate that at least 74 percent of the sales should be at higher SEERs, not at 16 percent as recently reported by ARI.

WHY THE DIFFERENCE?

Why then do many contractors still use the add-in equipment differentials? We can assume that they do not realize what was just explained above. Also, our industry is notorious for assuming the consumer will only buy the low price. The contractor may typically be afraid of price. However, this should not be the reality, as historically 80 percent of the consumers will purchase something of greater value if presented with the choice and a reason to buy it.Therefore, when we present a choice to the prospect, we must be careful to always present the value first and not just the price or the price differential. We must differentiate the SEER by talking about utility savings but more importantly the comfort differences such as variable speed, better dehumidification, and better air filtration, etc. People will always purchase something of greater value if given a reason to do so.

So, the way manufacturers might increase their share of higher-efficient products is to recognize that HVAC contractors are not sophisticated retailers. However, HVAC contractors are astute enough to recognize little value in promoting high-efficient products that increase gross revenue only to reduce profits (even if only percentages) and increase taxes.

Manufacturers might better help the contractor to shed the add-in differential price methodology during their training sessions that they already provide. Not that the manufacturer should be directly involved with the contractor’s pricing, this is the contractor’s realm, but it could provide training or at least some guidance in better positioning the product offering to increase sales and profits by capturing all the contractor’s costs.

The contractor needs to abandon the add-in differential price methodology and price the products to capture all these costs. Perhaps the use of flat-rate equipment and installation pricing should be incorporated.

The major weakness of the use of the add-in differential price methodology is that it does not allow for the capture of all costs. Recognizing that your overhead, profit, etc. are all based on your gross revenue (the selling price not the costs) and is a percent there of, is essential to improving contractor profits and higher-efficient product sales. Understanding and applying these principles may be the key to increased market share of higher-efficient products to levels that the manufacturers expect and in the process provide better comfort to consumers and deserved profit levels to HVAC contractors.

Publication date:01/21/2008

Report Abusive Comment